Thinking Inside the Box: 1973 is a project that came to the University of Leeds in October 2022.

The motto of our work has been to "think inside the box" - to reawaken hopes, struggles, and solidarities of the past through a performative engagement with the archive. To mark 50 years of the Chilean military coup, our exploration of the archive has been guided by the year of 1973, but is not only focused on Chile: in the context of the Global Cold War, 1973 marked a critical political moment for many other Latin American countries.

This exhibition was first launched at the University of Leeds on 18th April, 2023.

Click on the images below to learn more.

Did you know?

In 1976, a mural was painted in solidarity with the people of Chile at the University of Leeds’ student union. Find out more here.

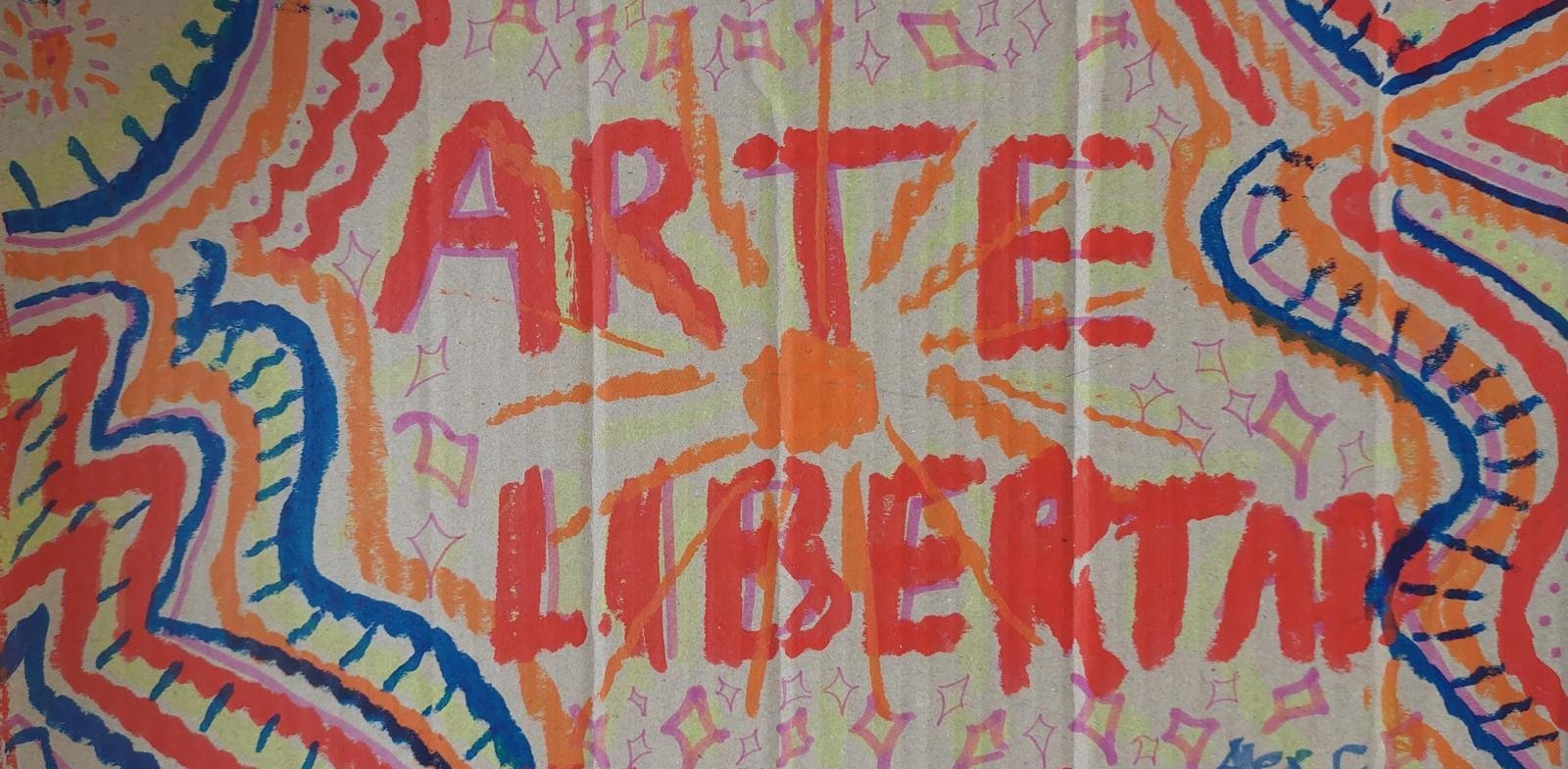

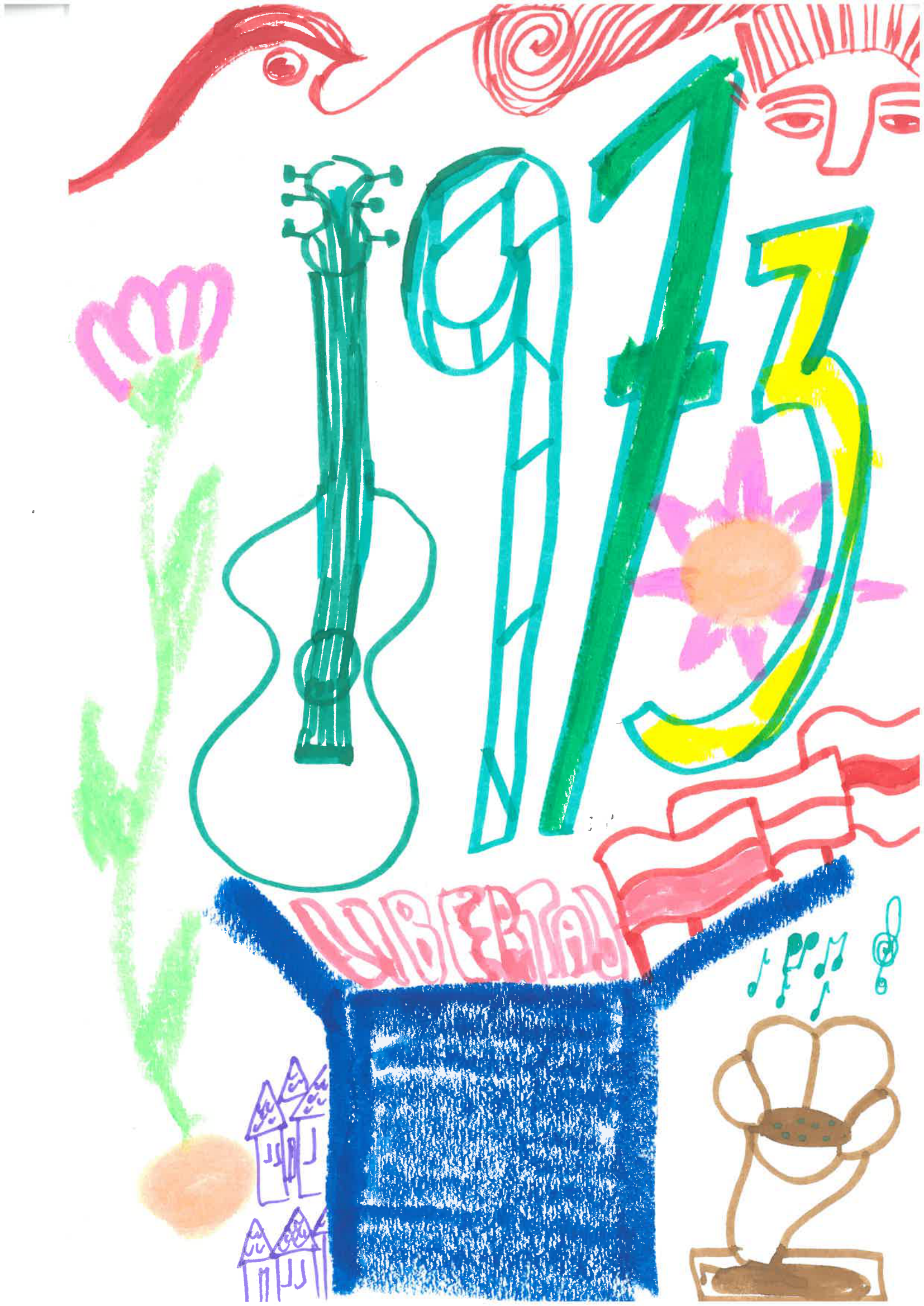

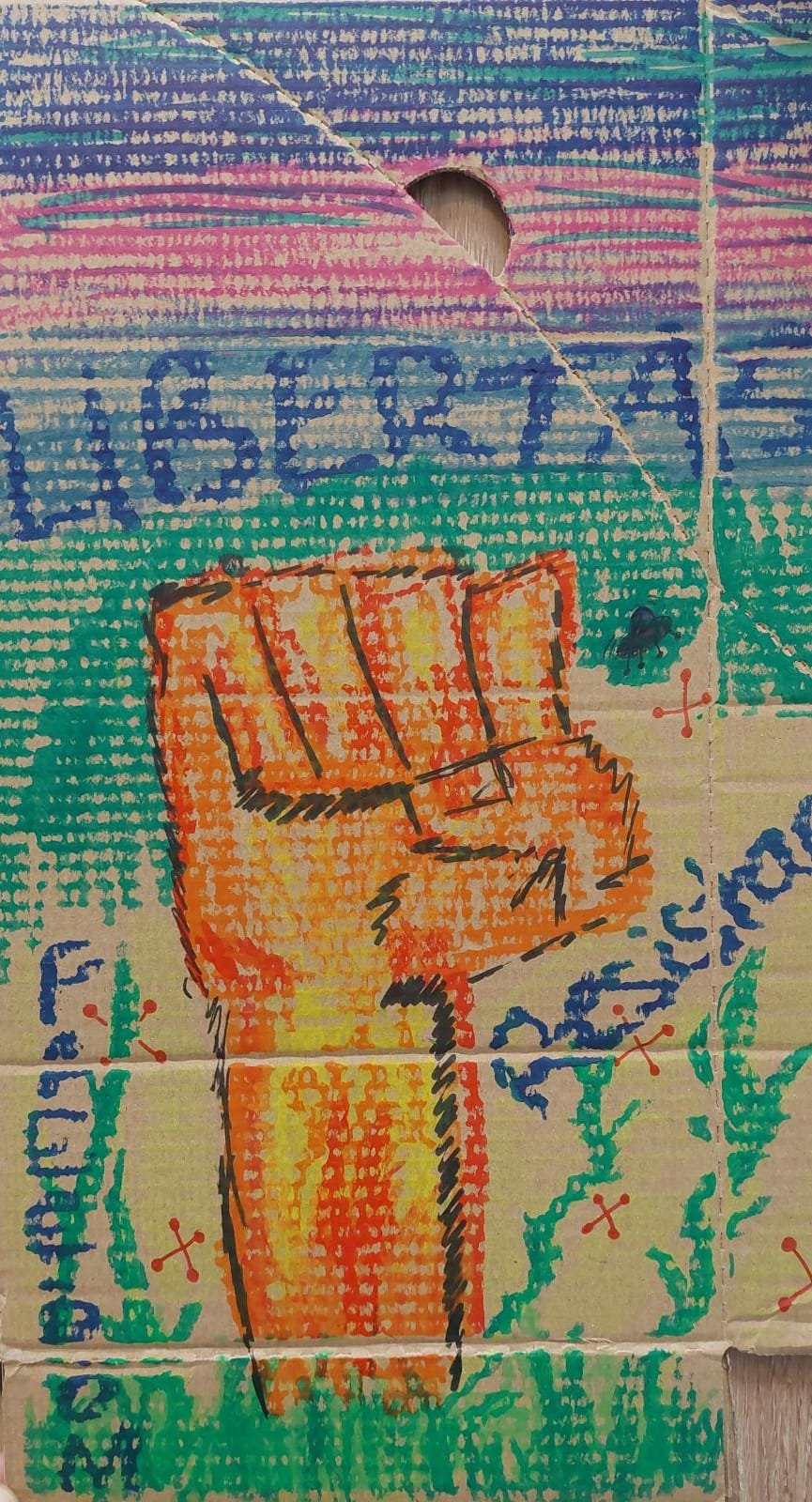

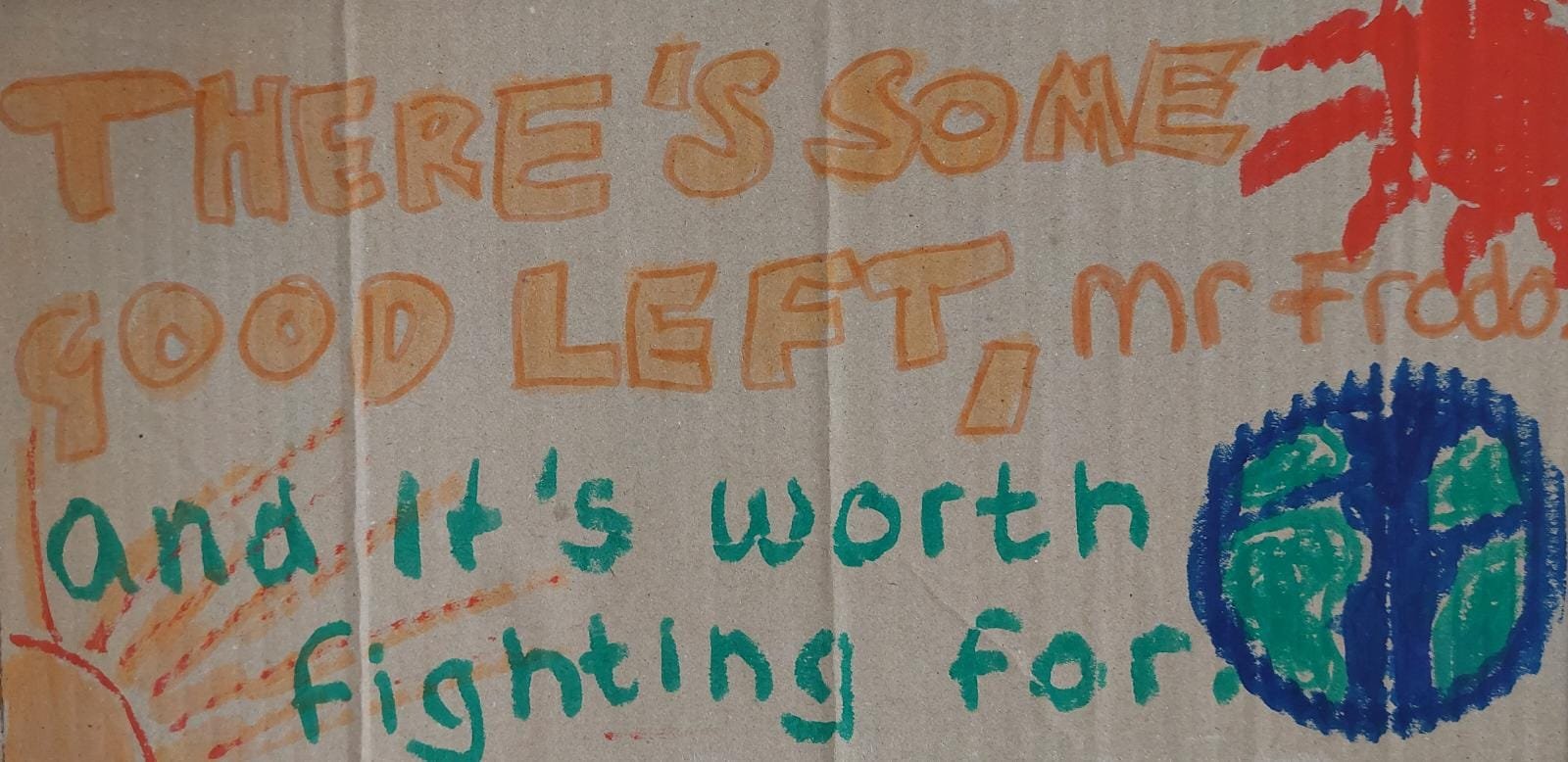

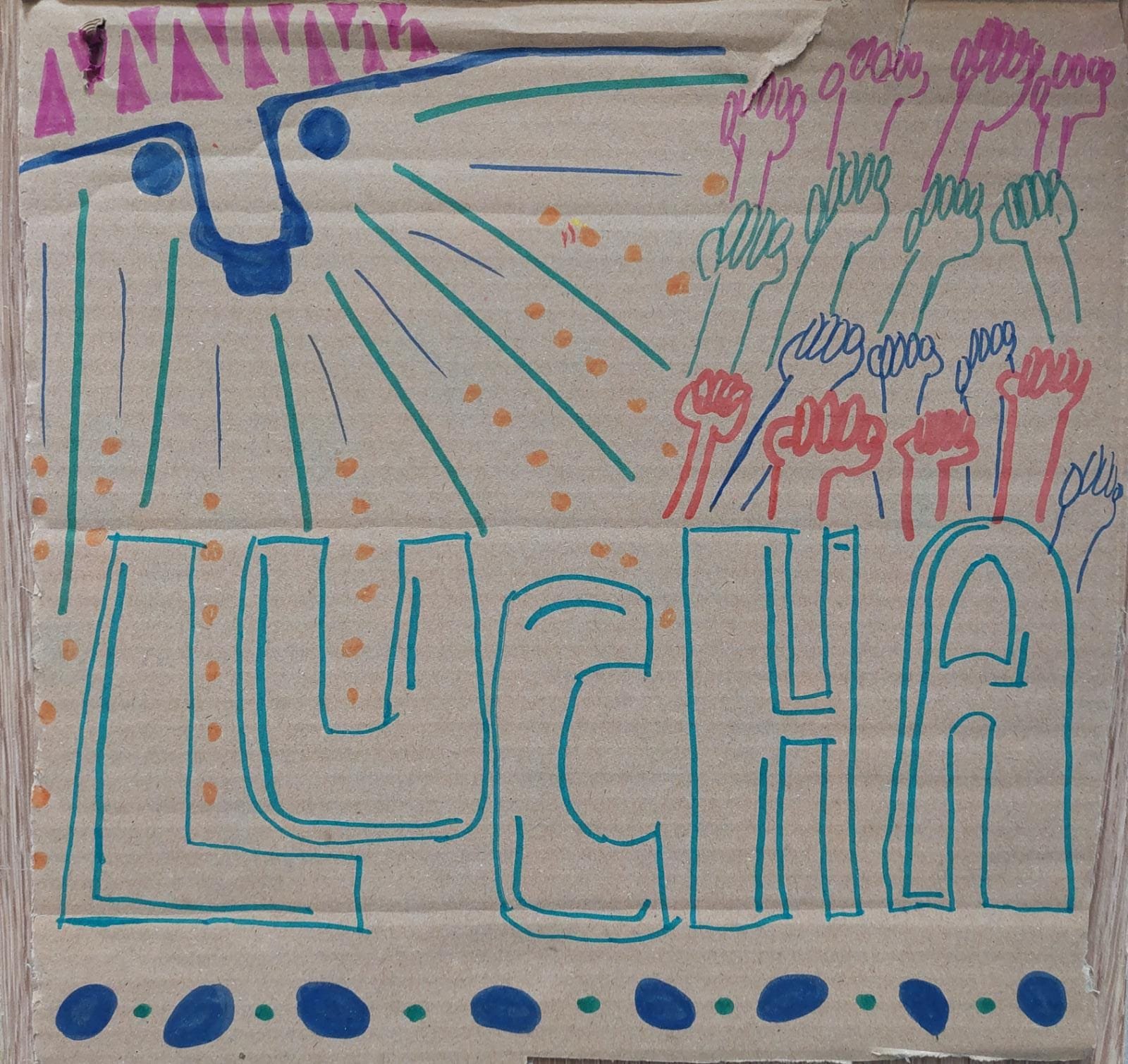

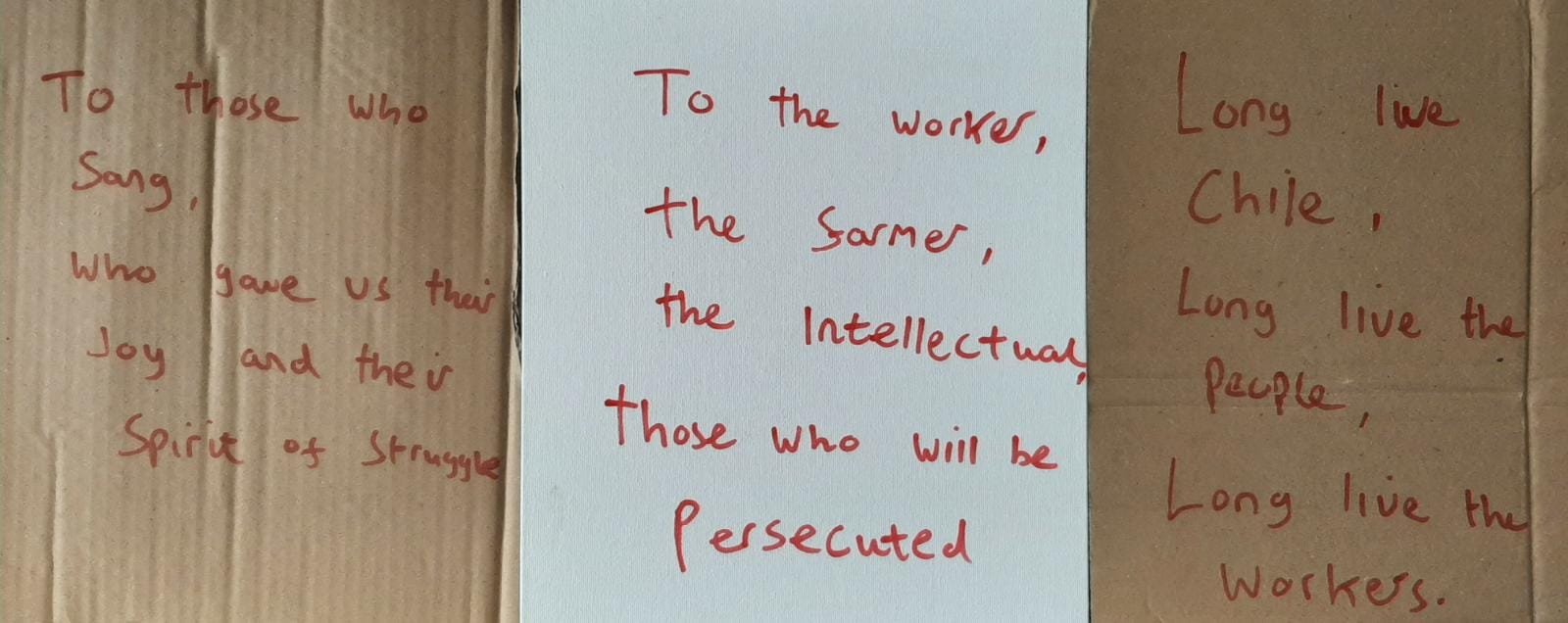

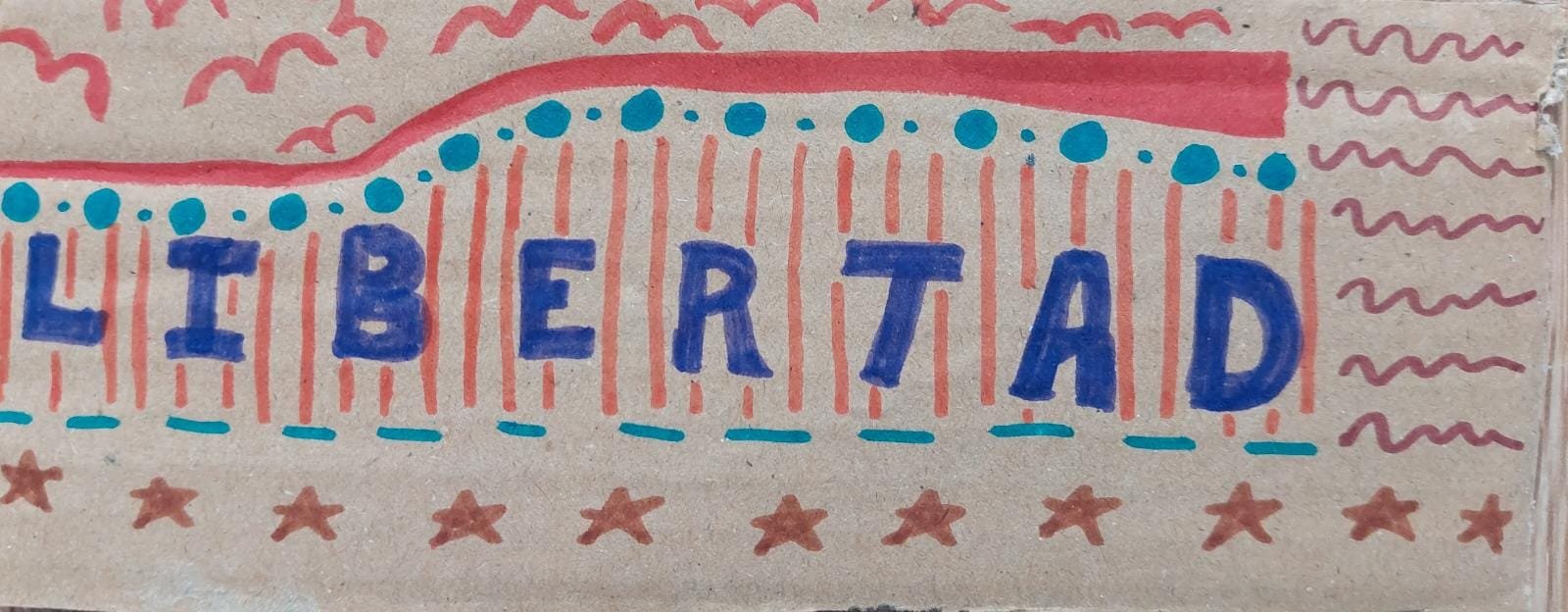

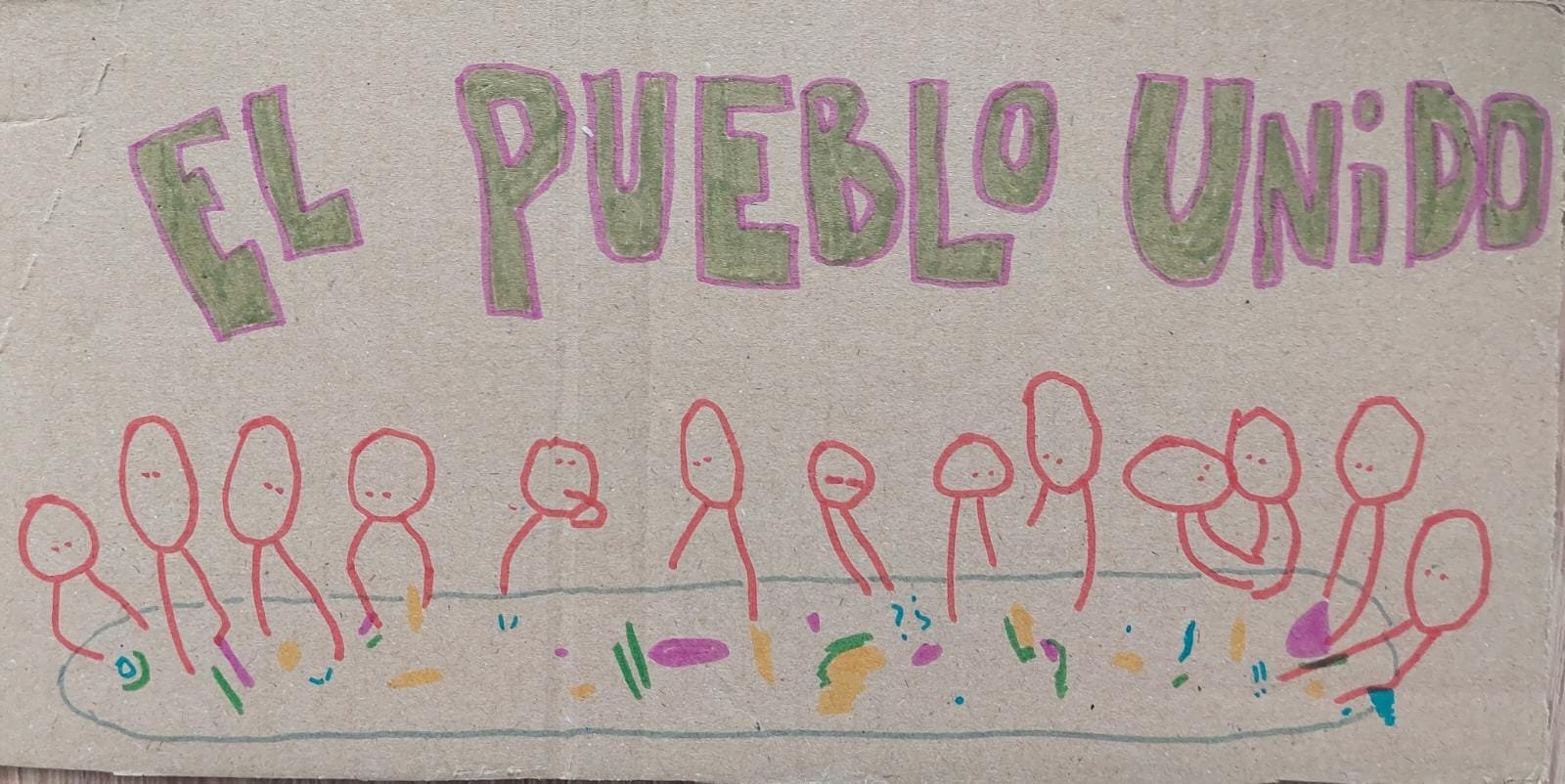

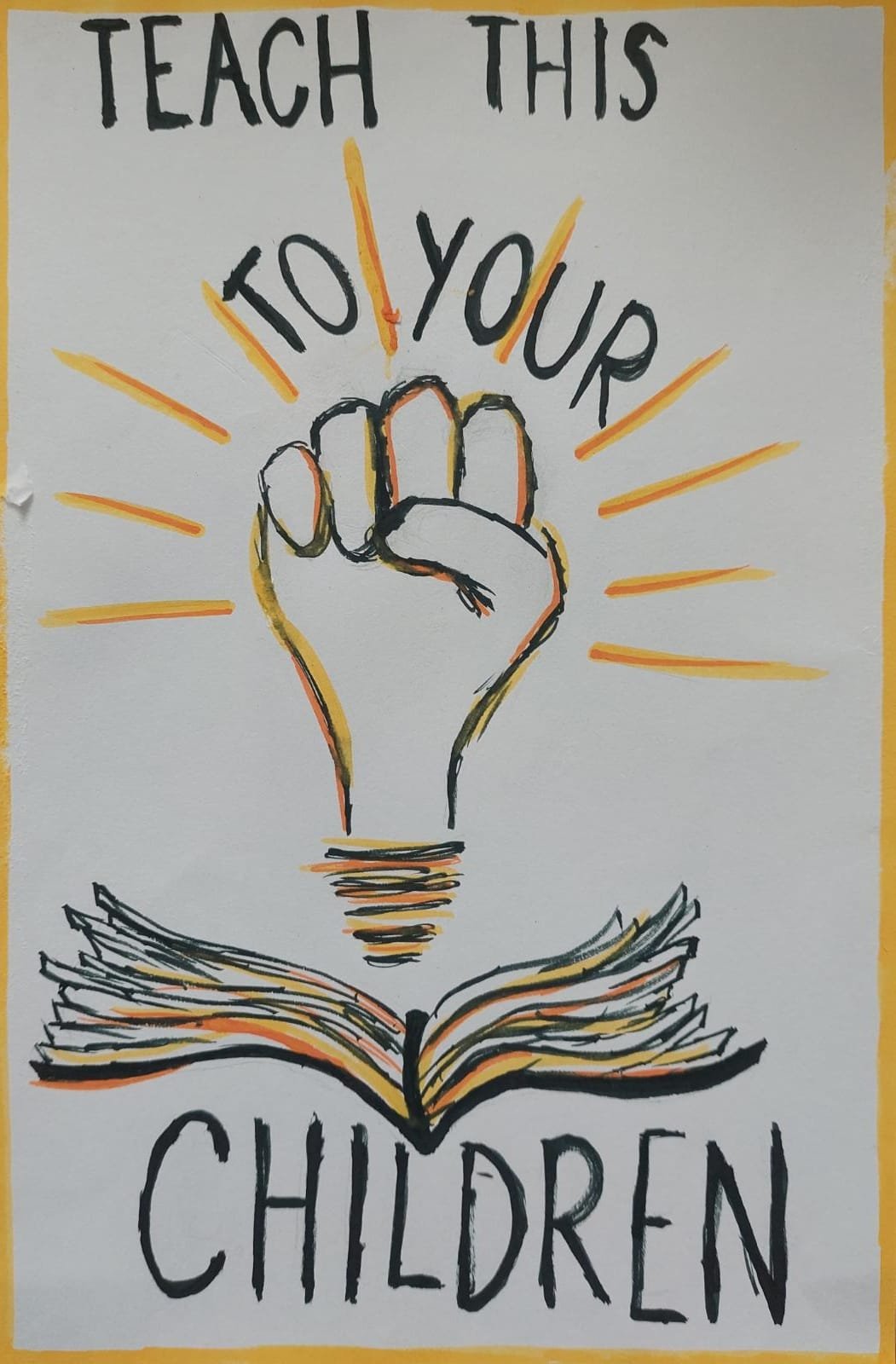

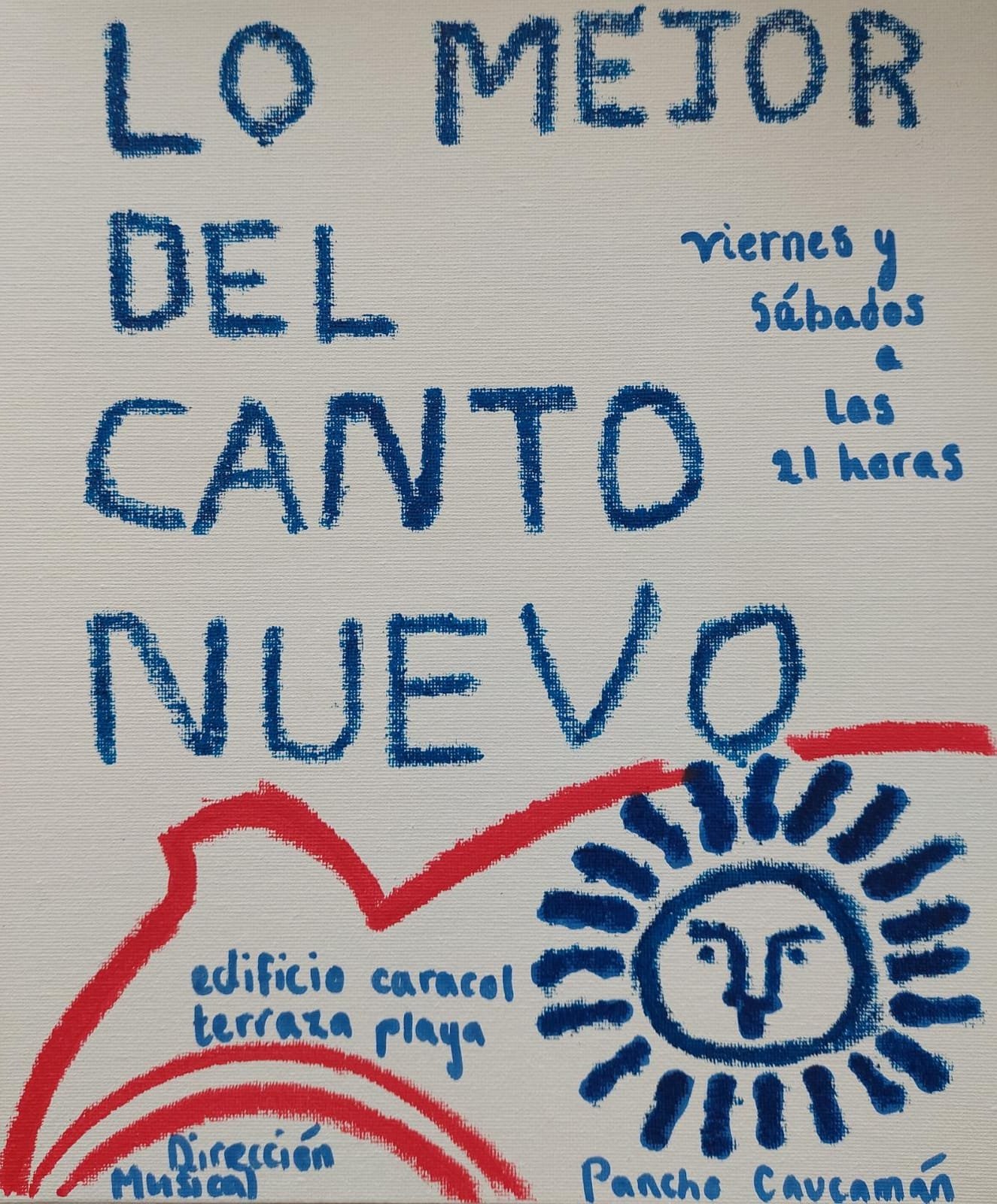

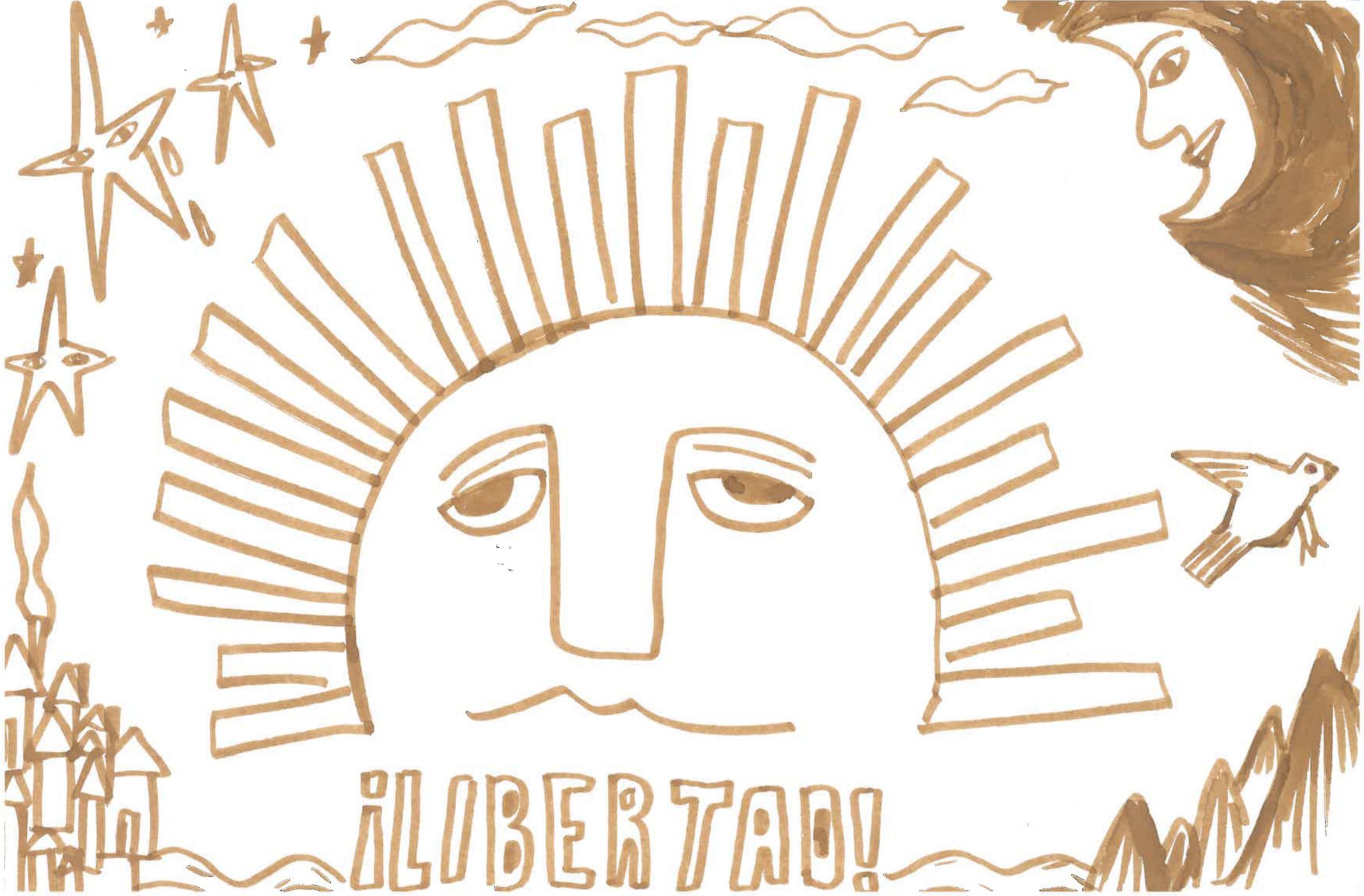

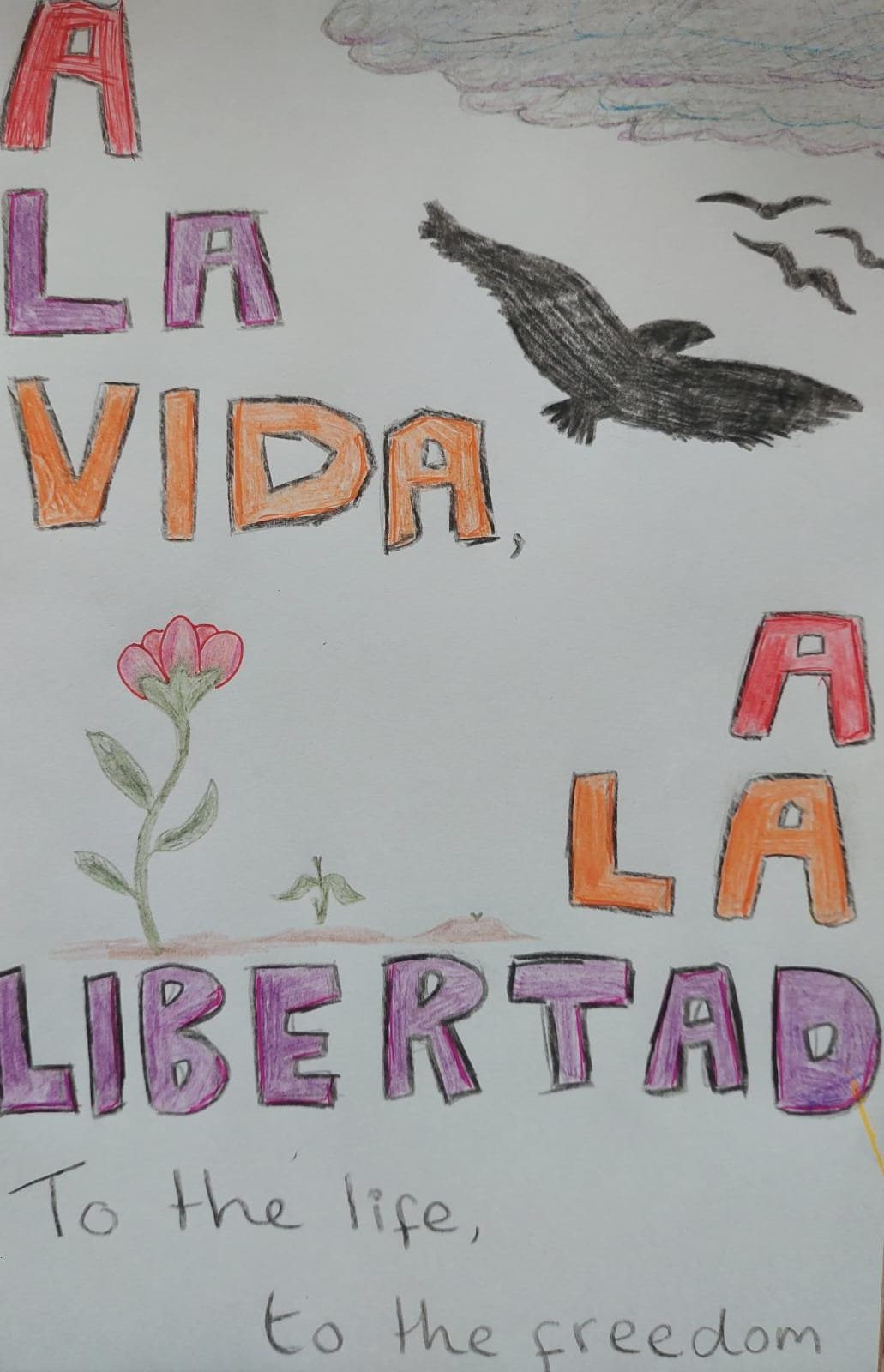

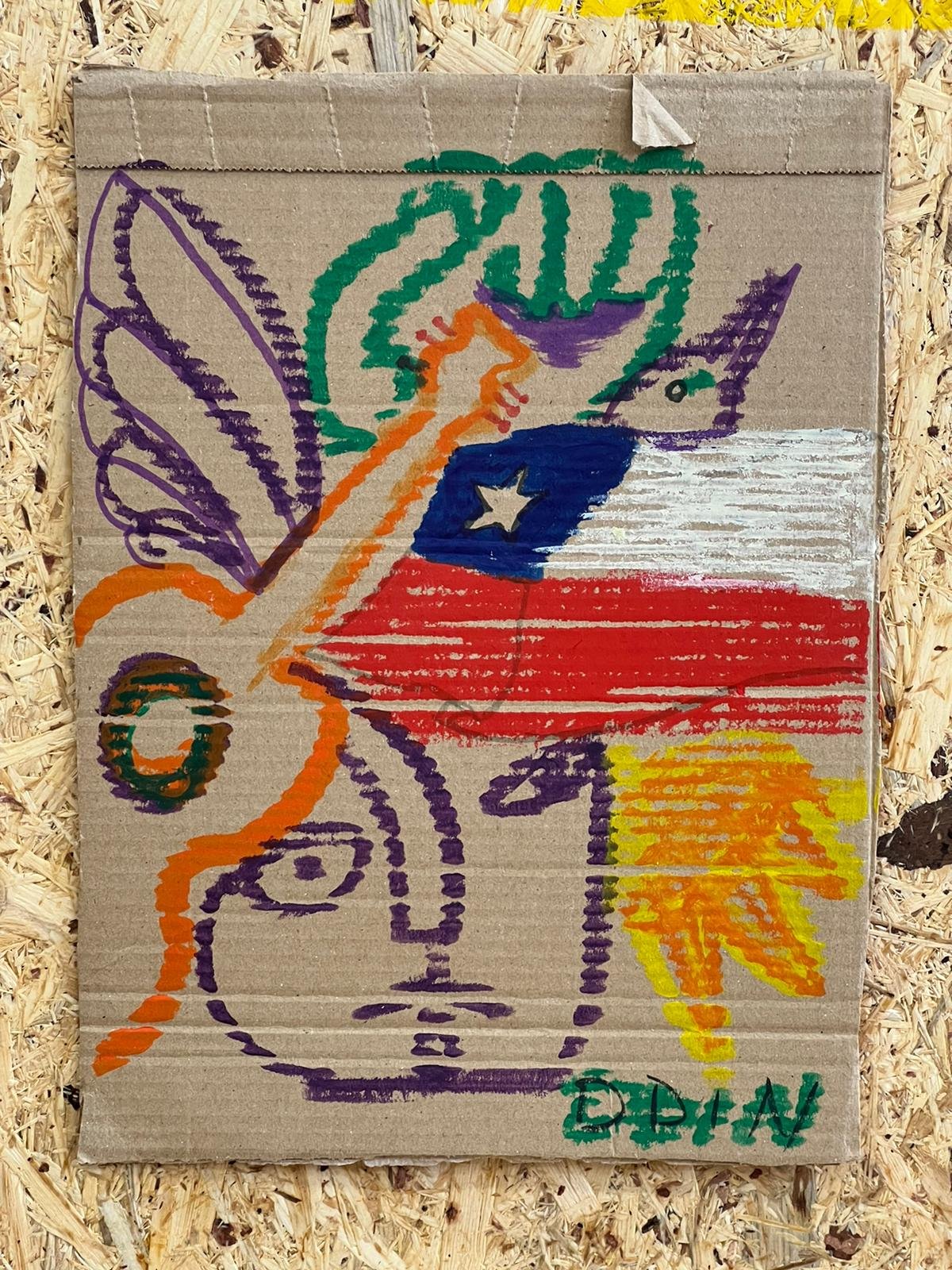

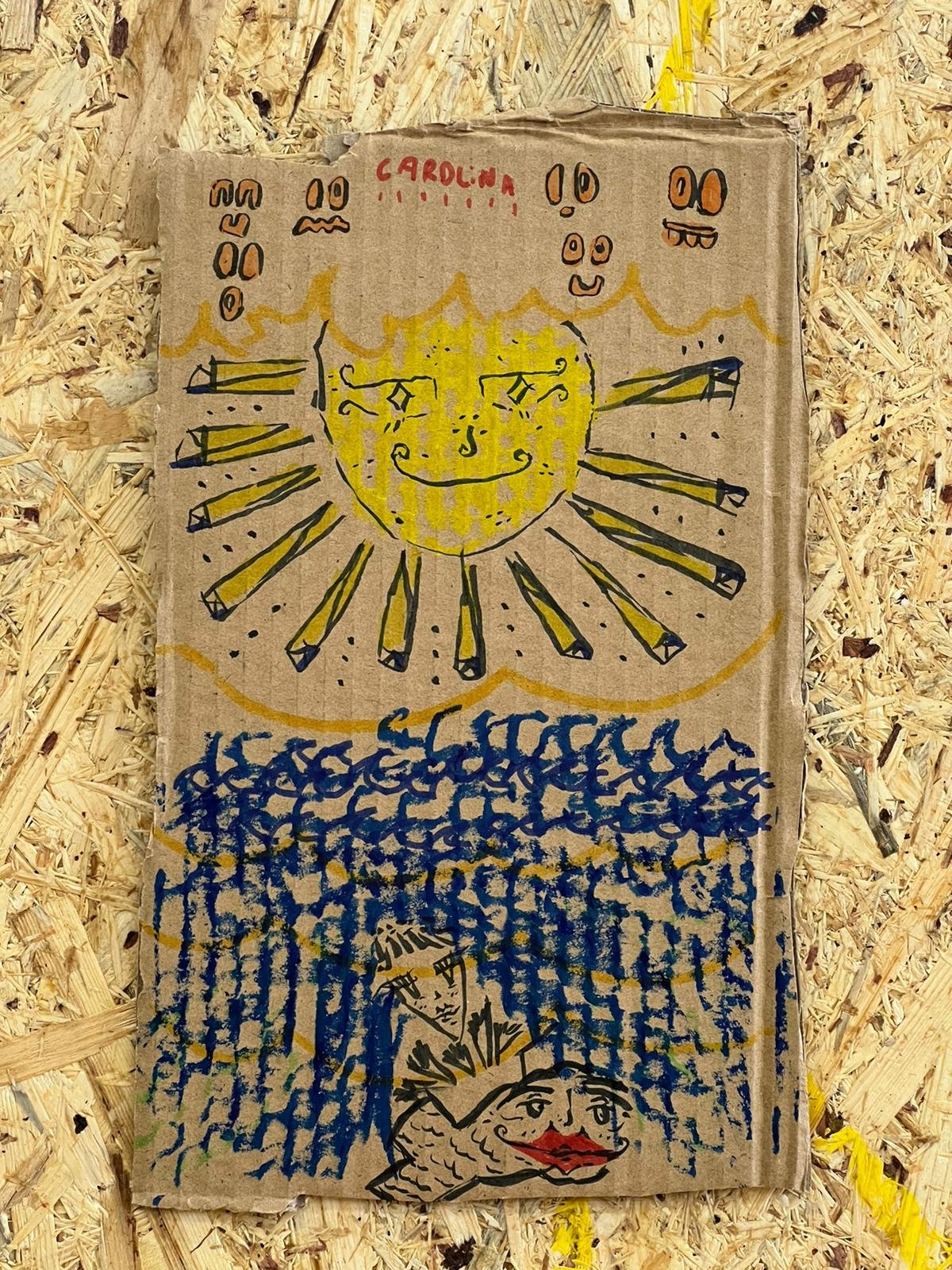

INSPIRED BY THE WORKS OF ANTONIO KADIMA, THINKING INSIDE THE BOX: 1973 HAS CREATED ITS OWN ARCHIVE OF COLLABORATIVE POLITICAL ARTWORKS.

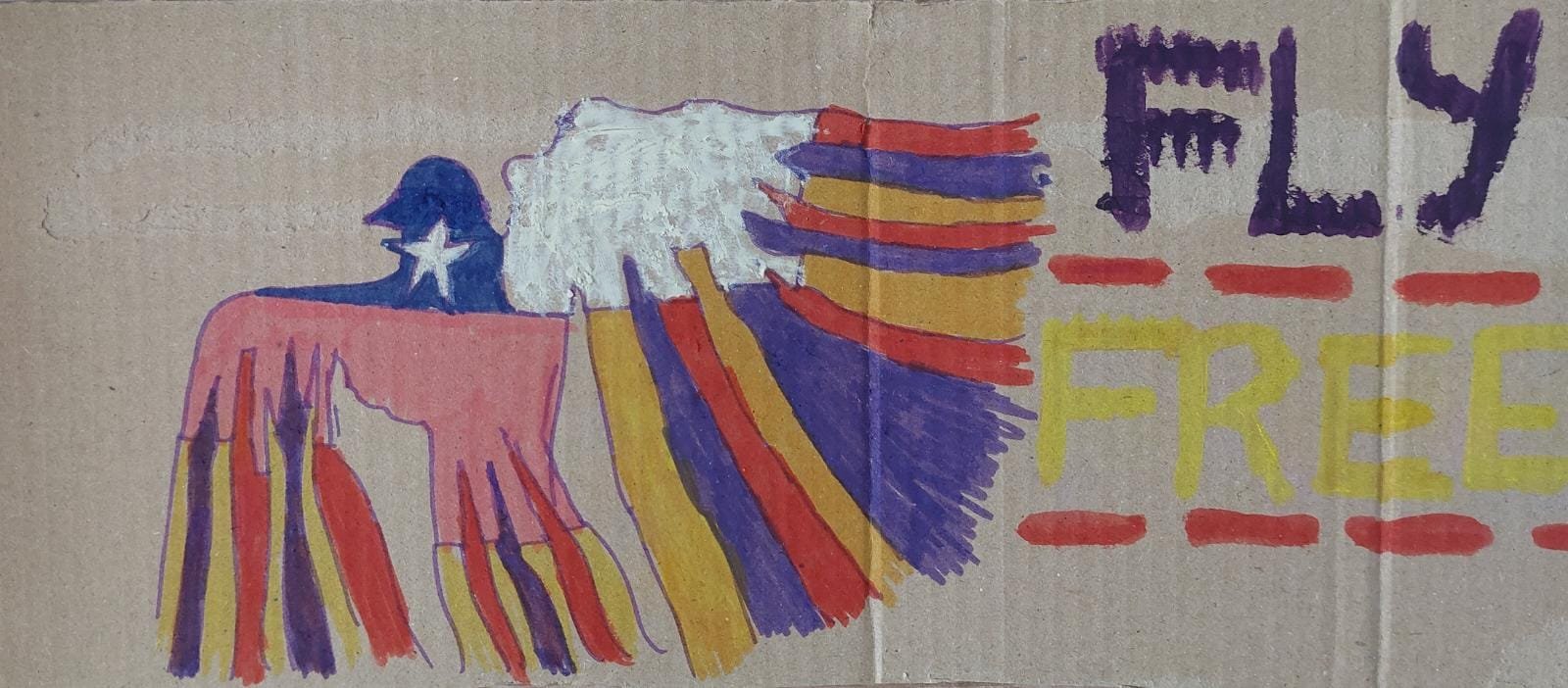

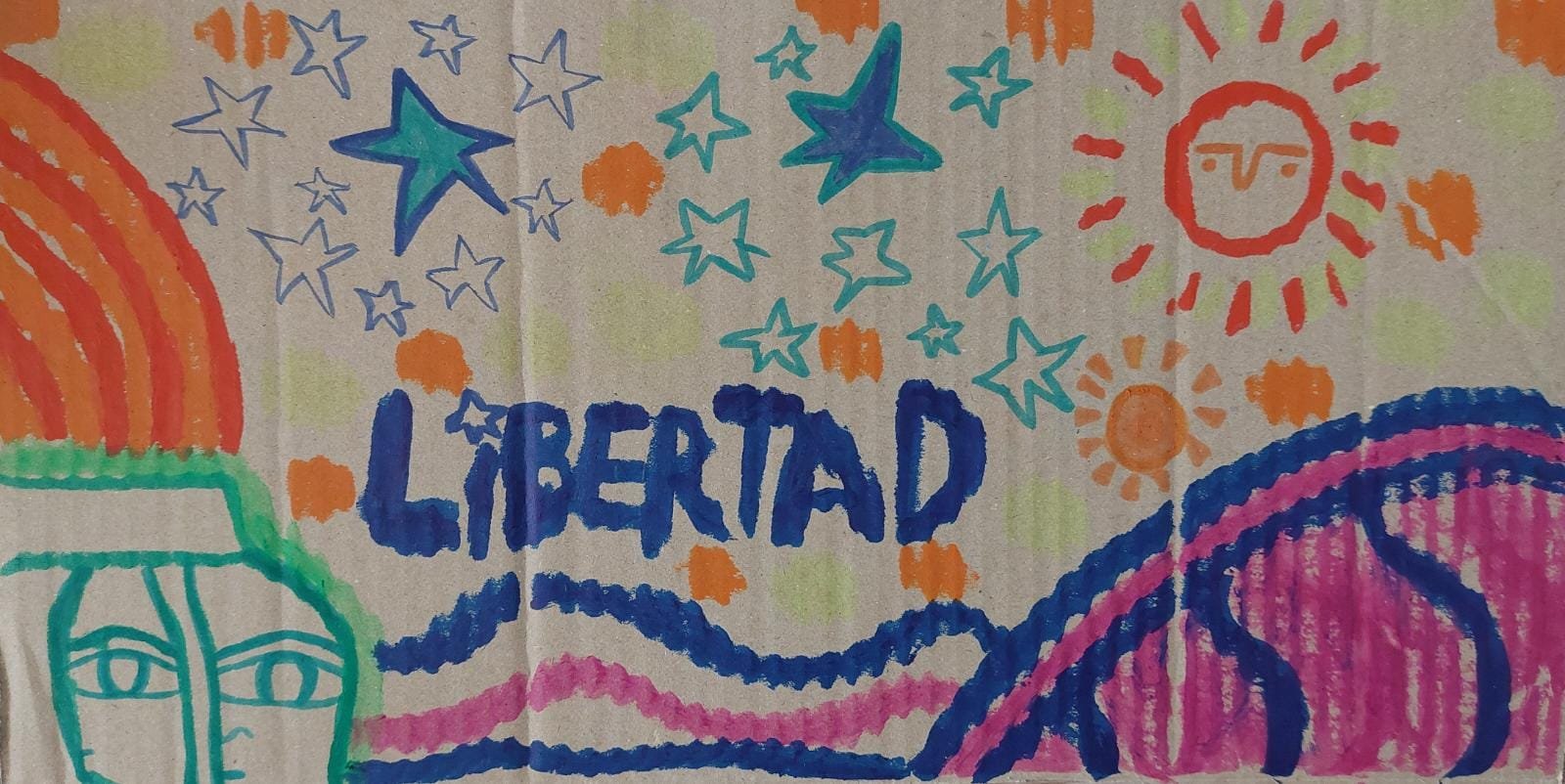

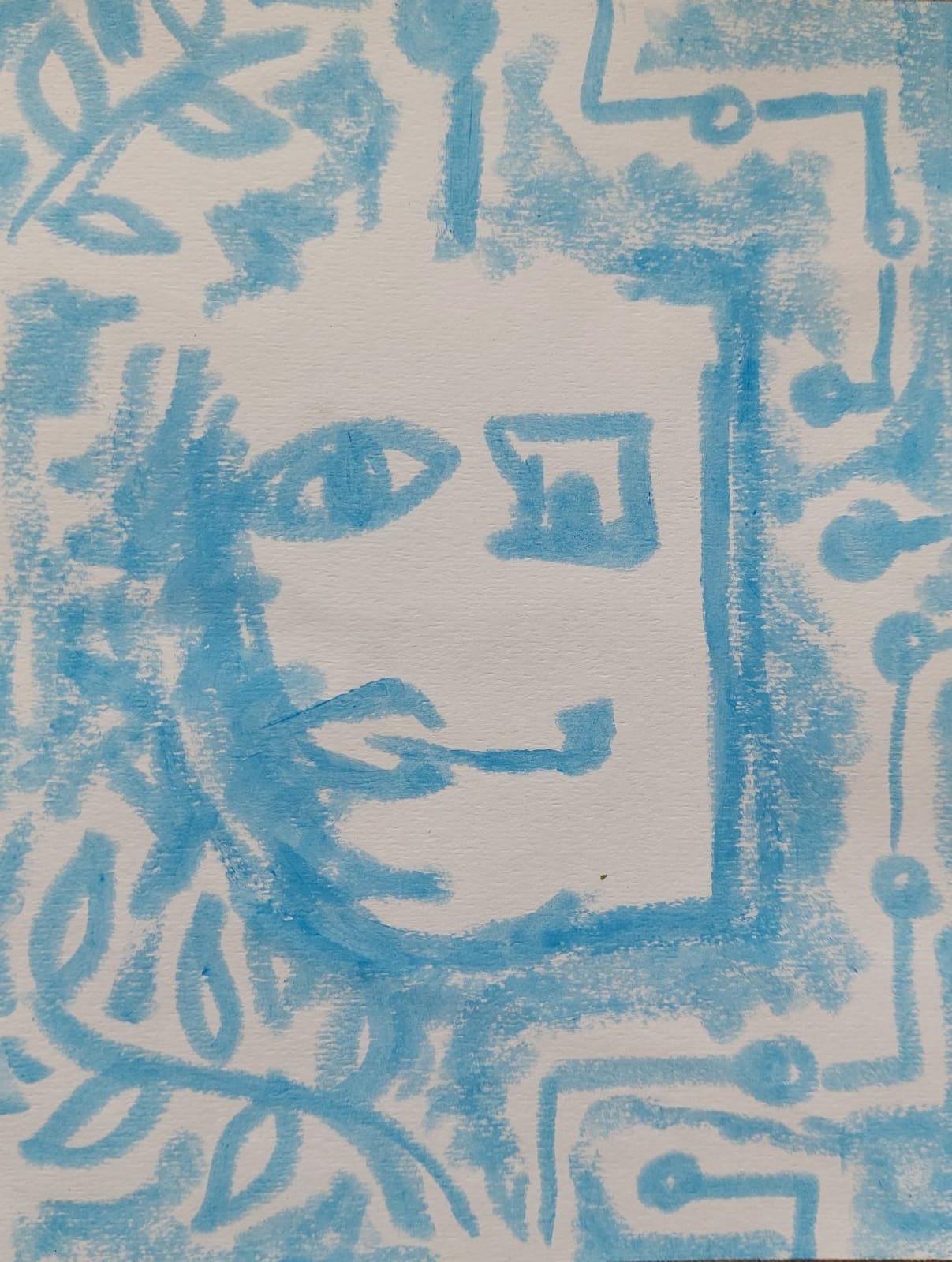

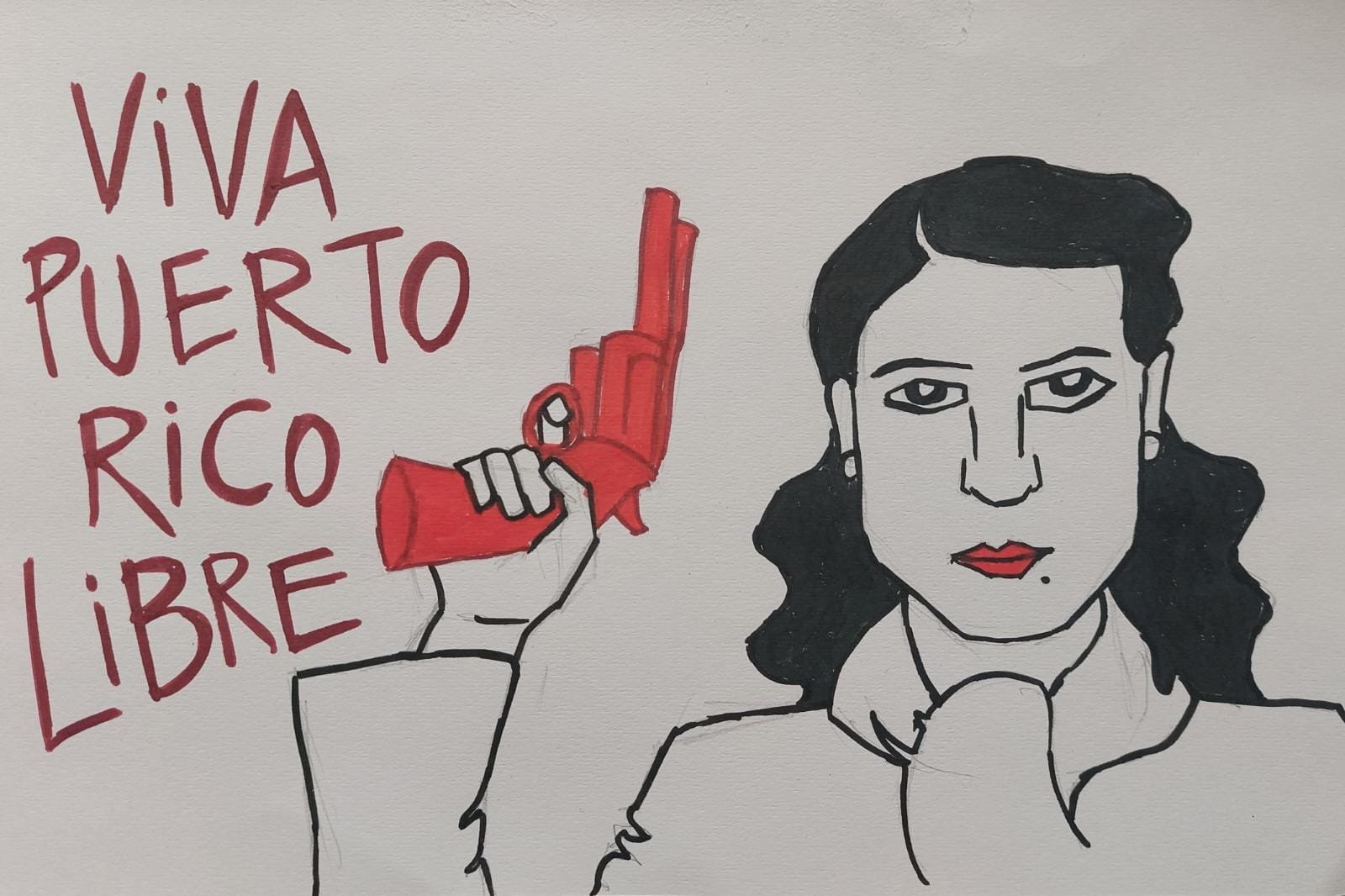

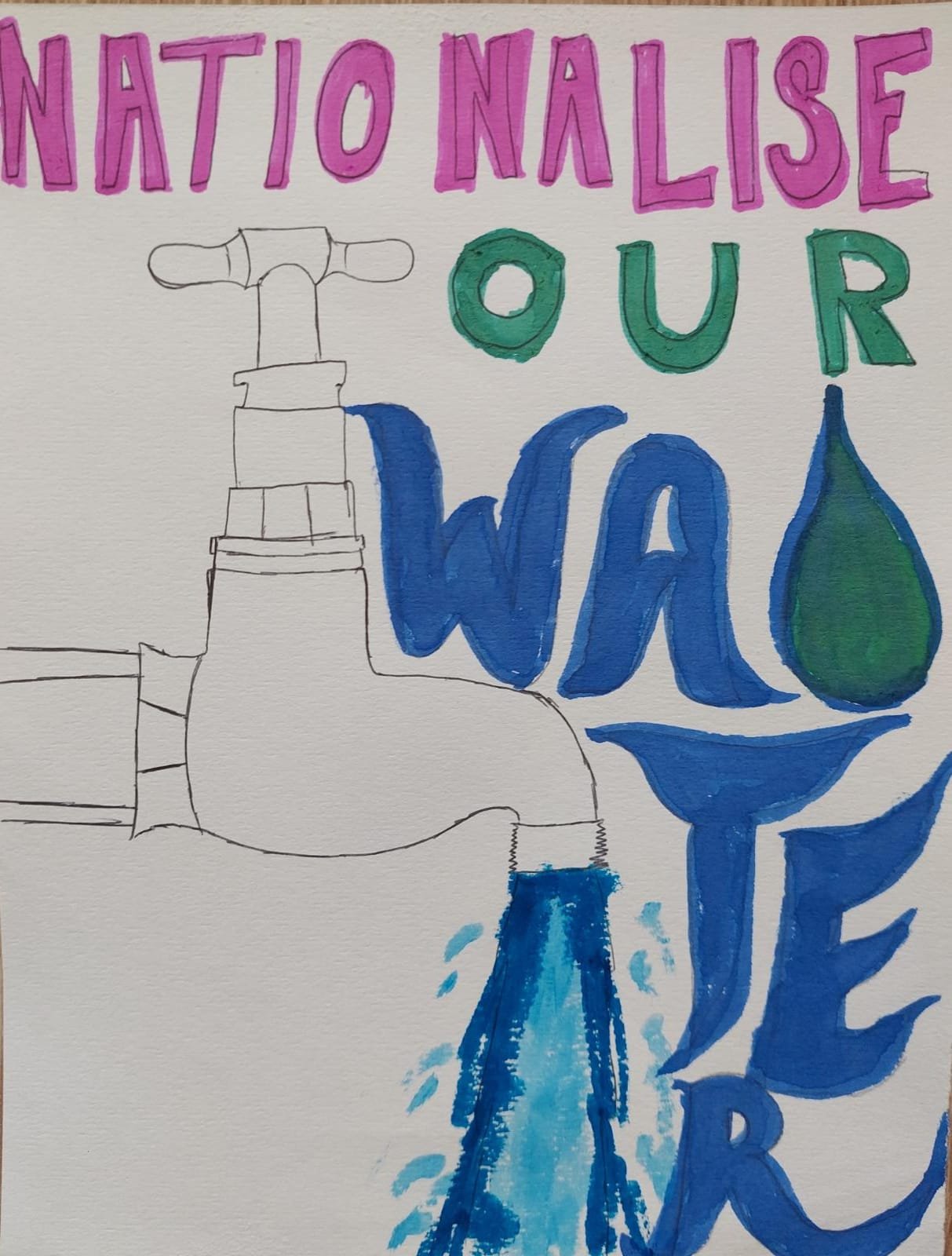

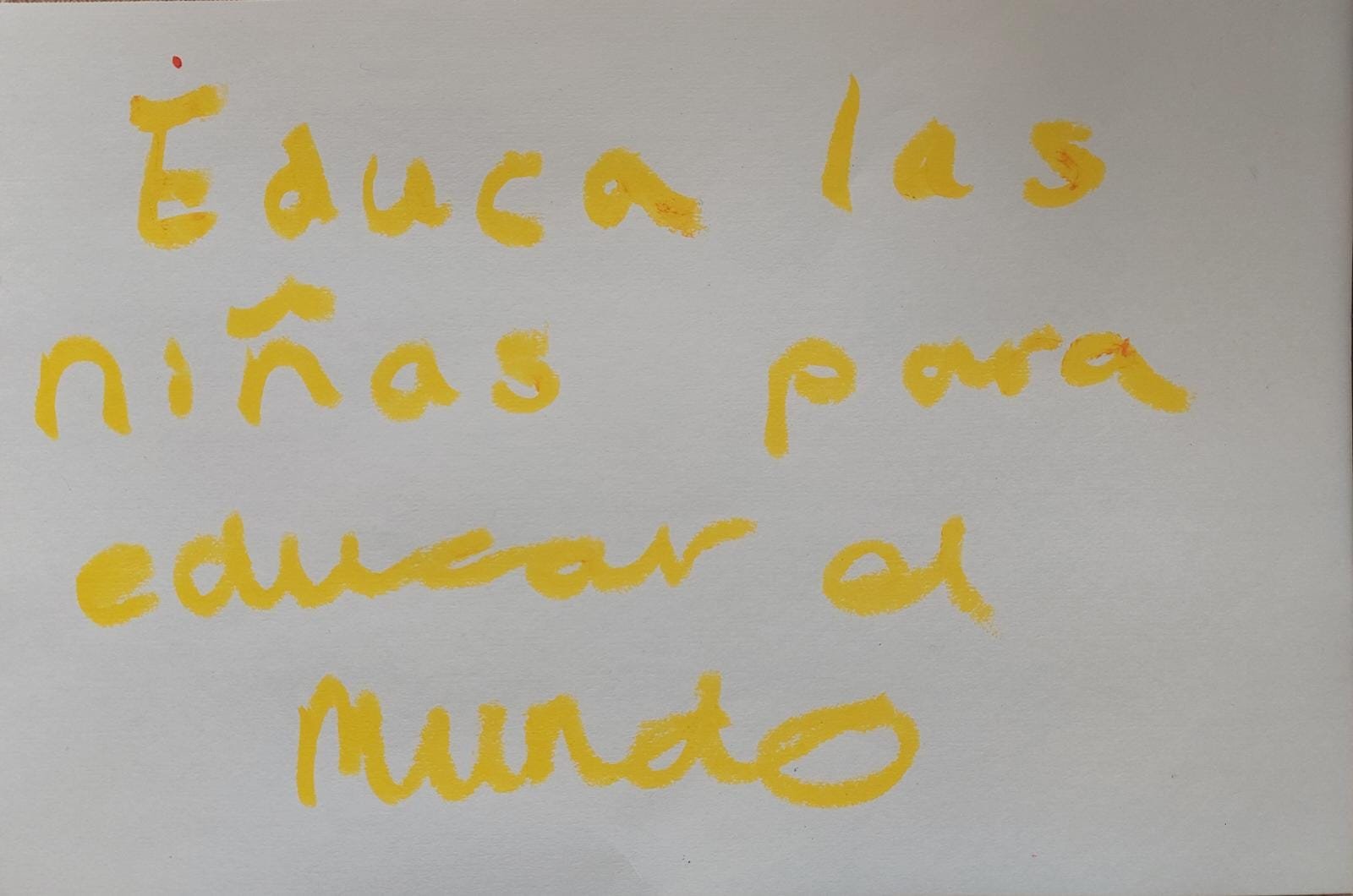

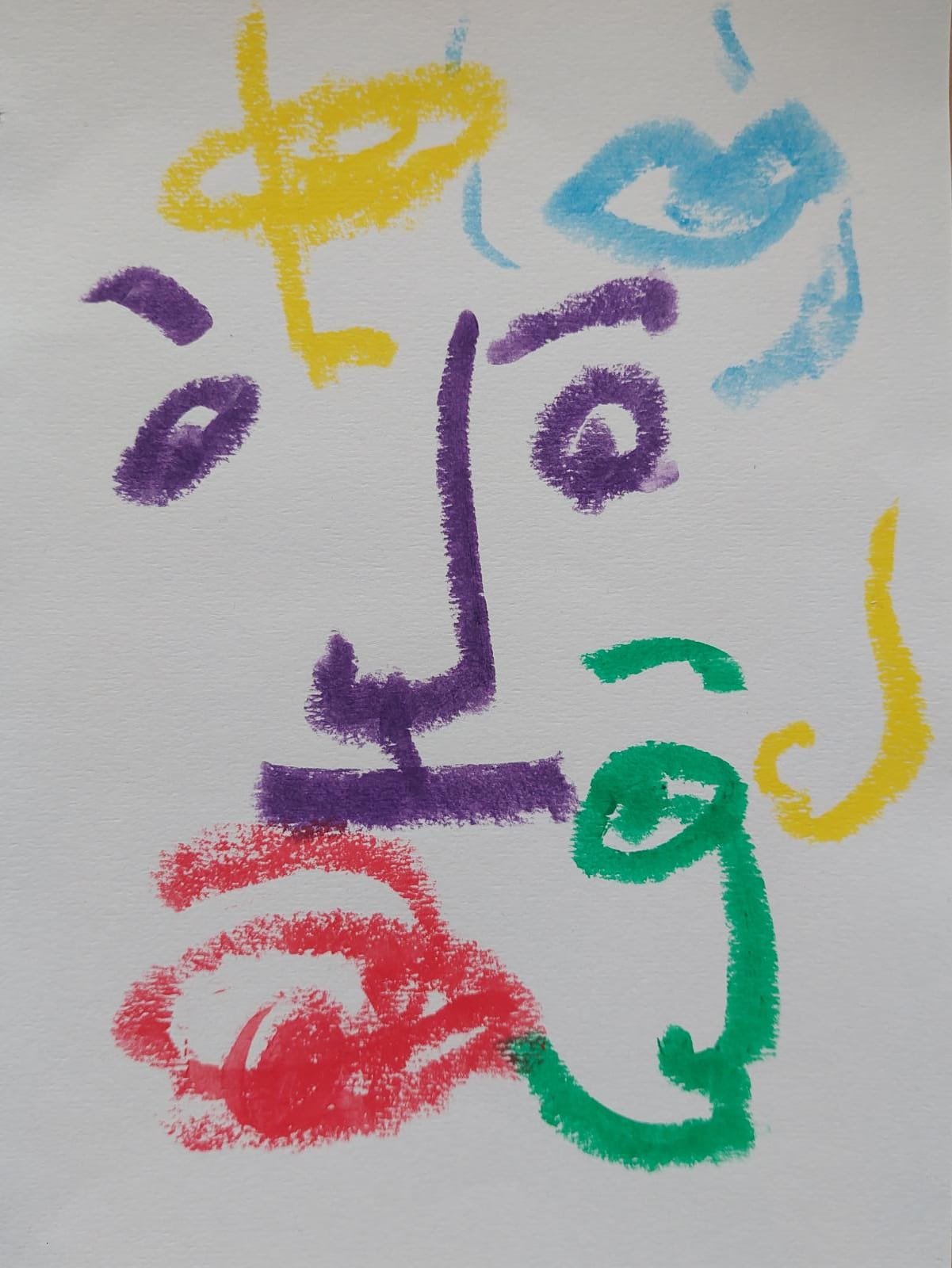

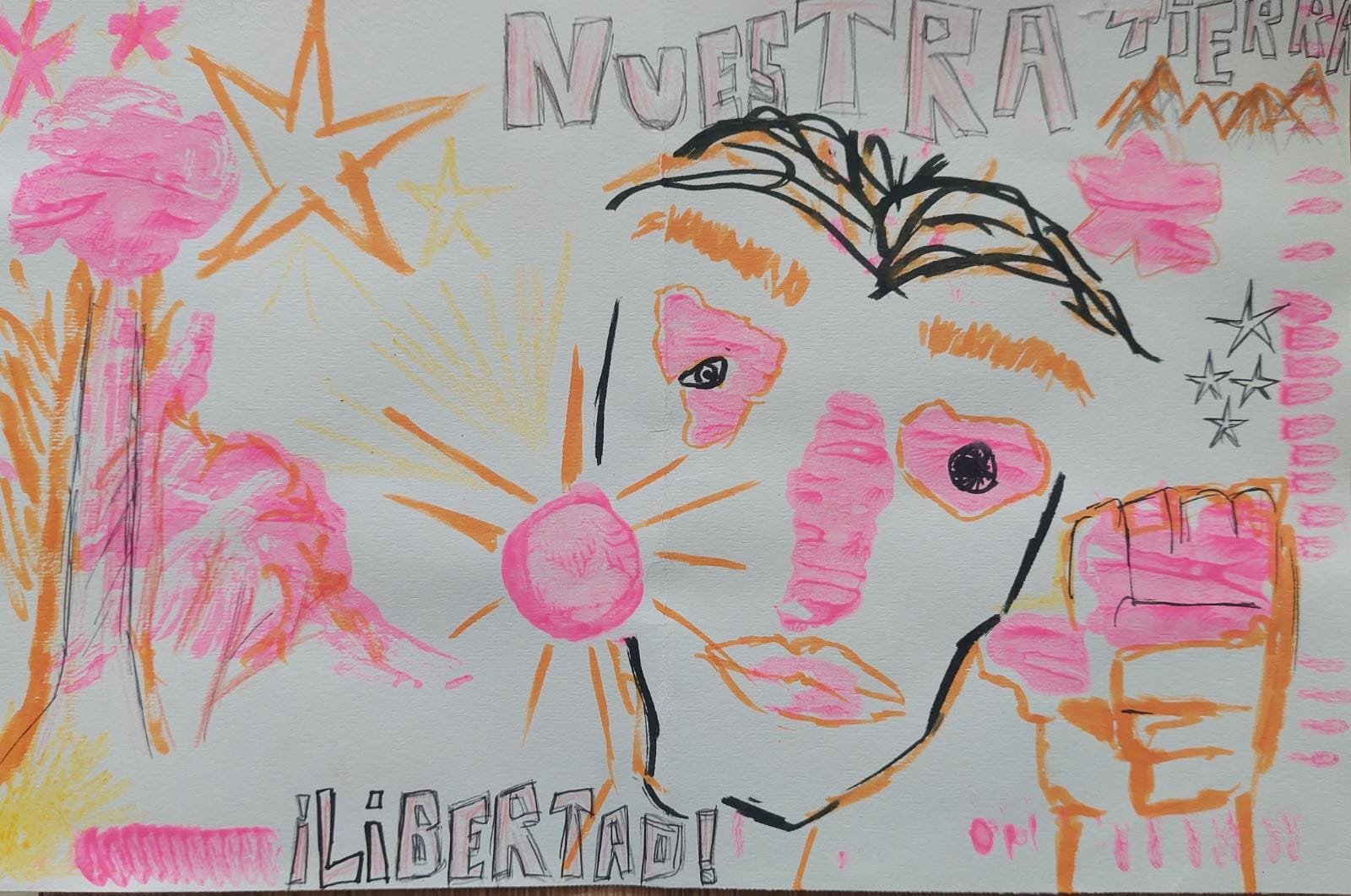

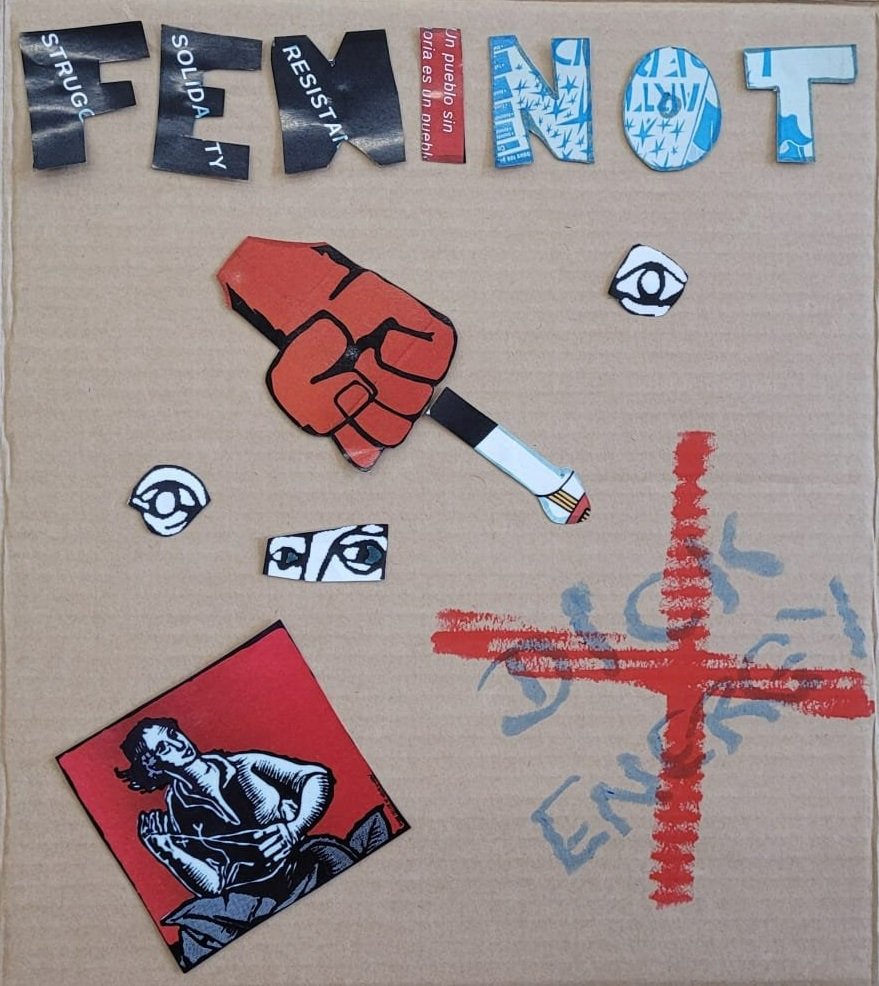

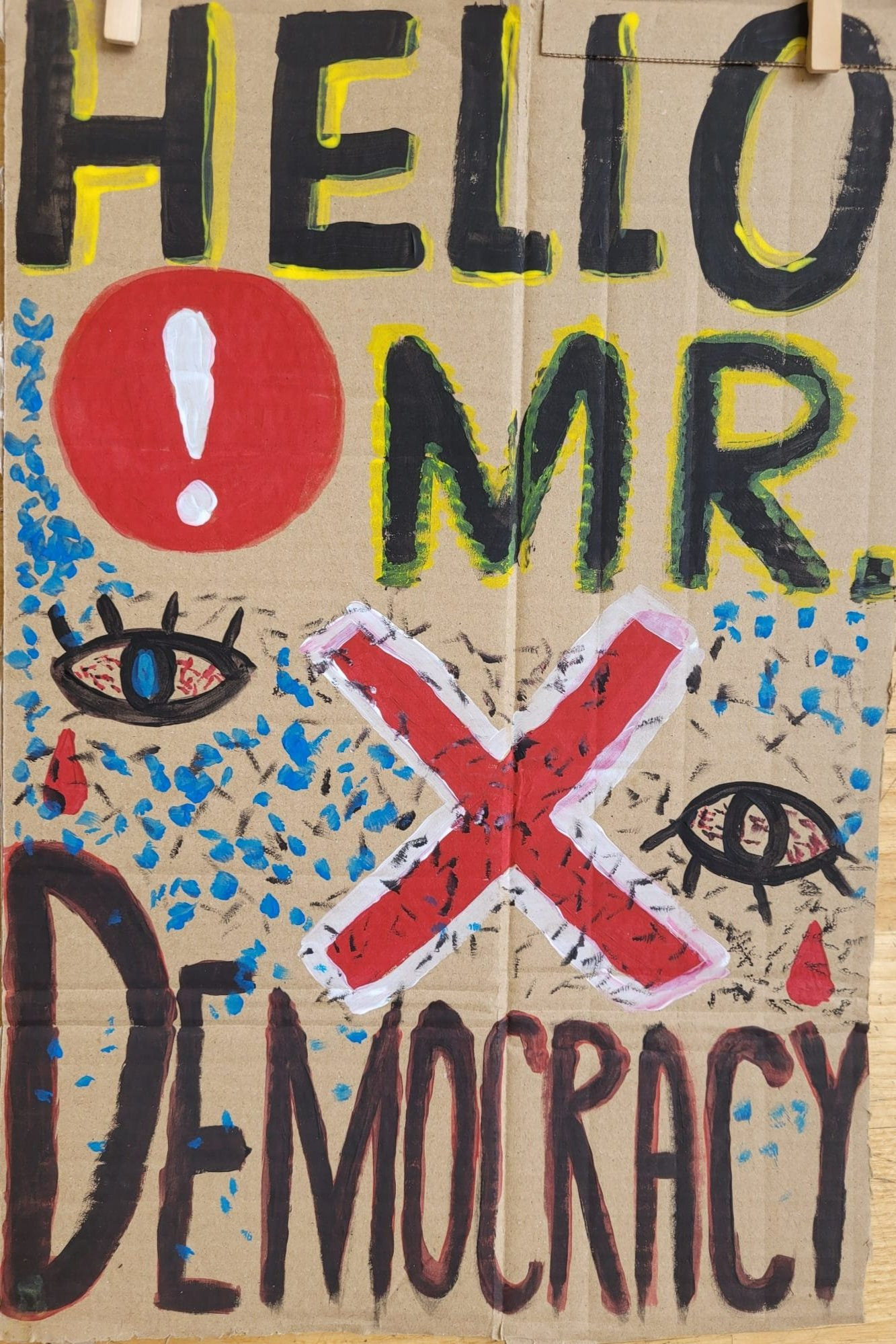

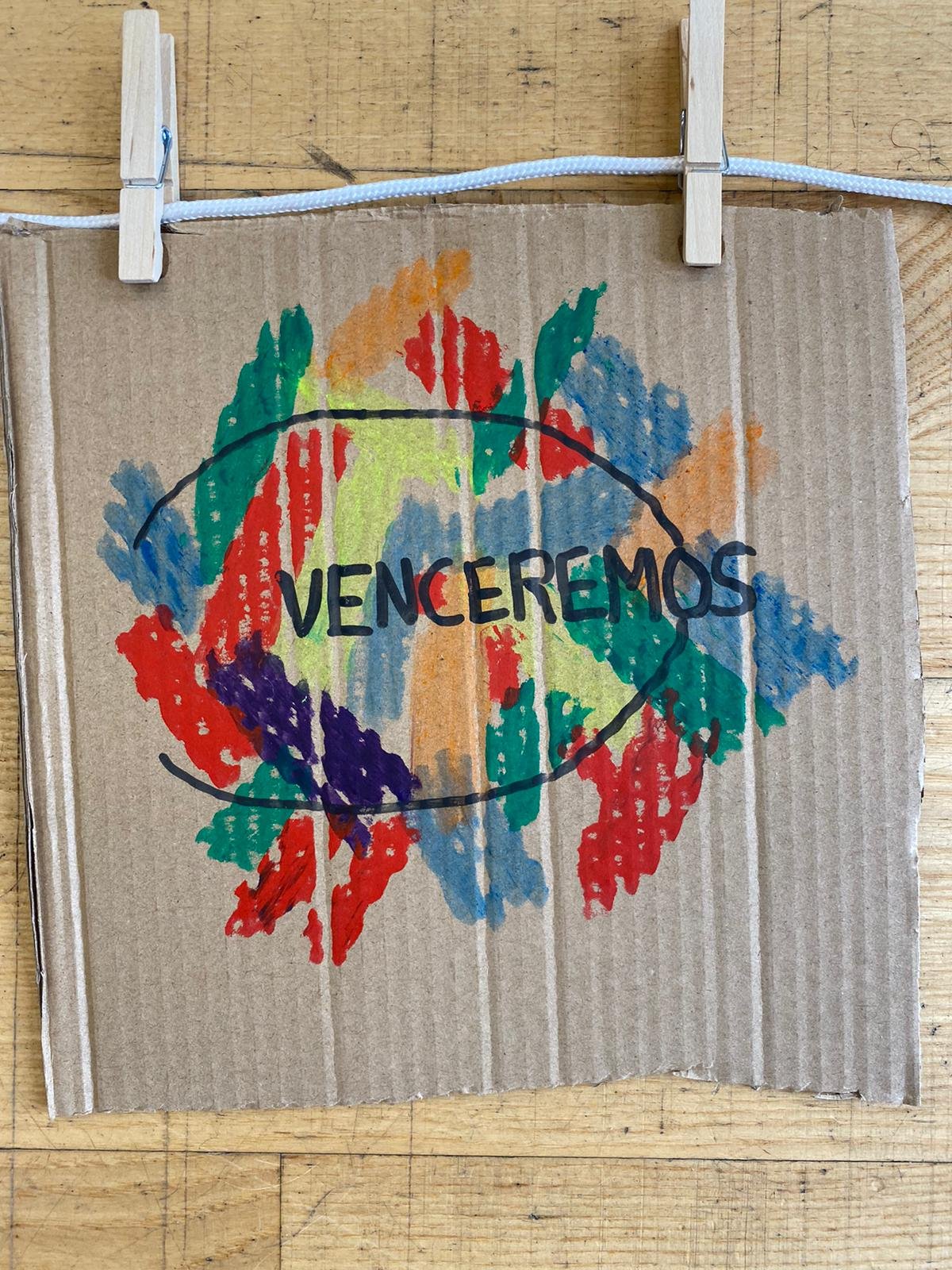

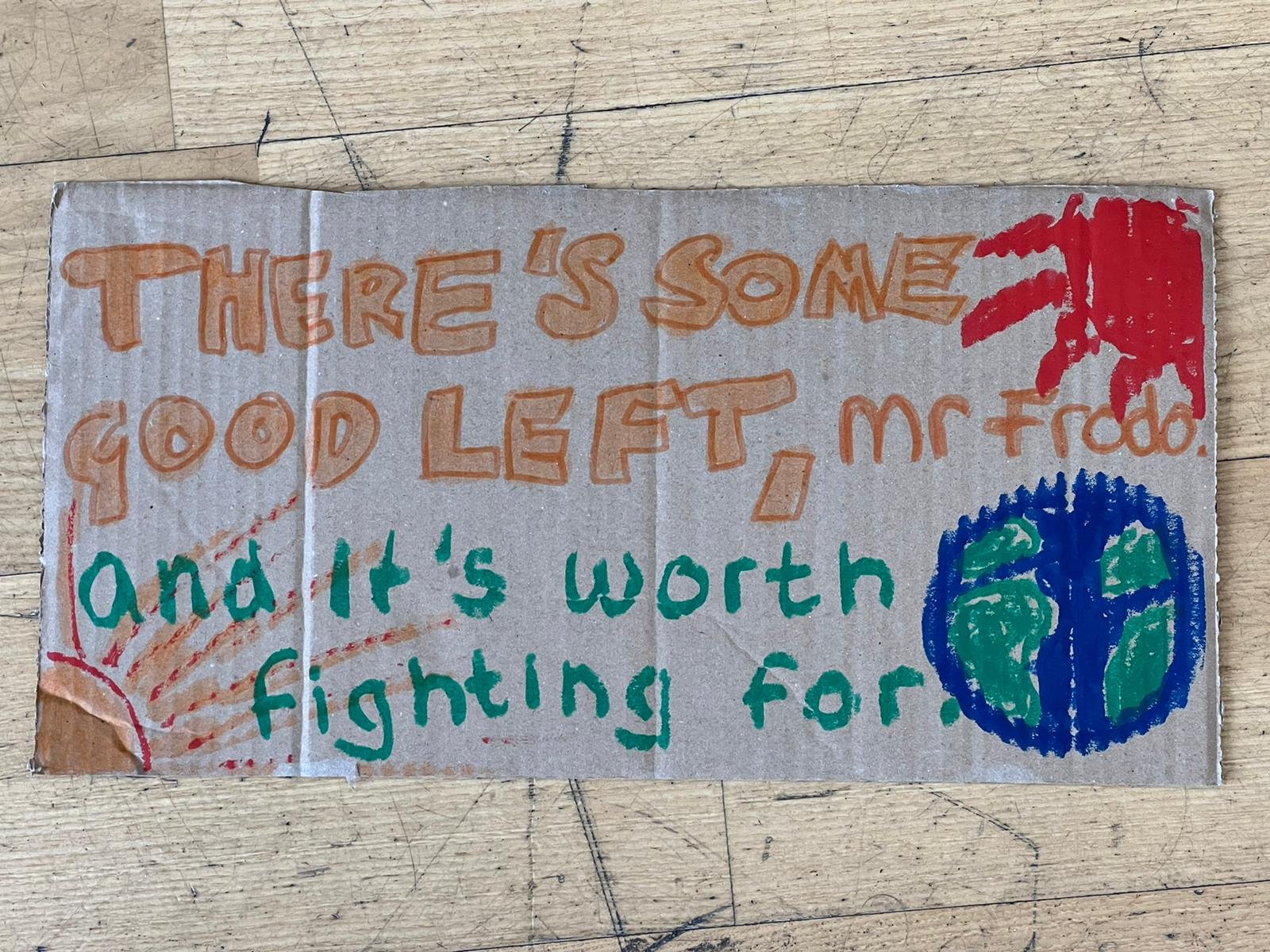

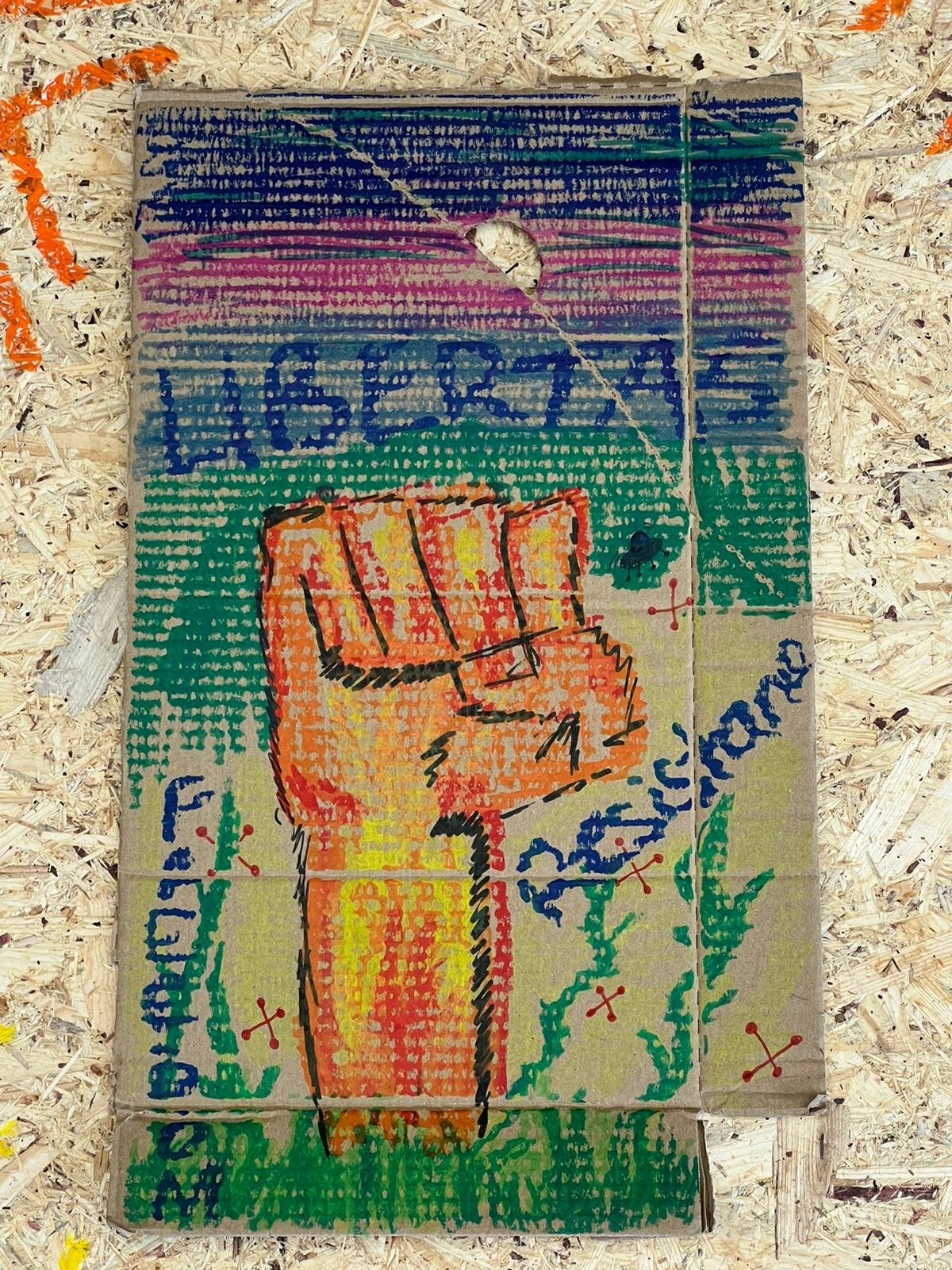

In April 2023, we’re running a series of workshops across Leeds to engage with a range of publics in collectively ‘thinking inside the box’. Guided by the theme of Hope, Struggle and Solidarity, we are drawing inspiration from the political artworks and printed material we have been exploring through the archives over the past months. By sharing these materials with our audiences, our goal is to reawaken the practice of visually representing hopes and struggles for a better future.

SCROLL DOWN TO SEE OUR COMMUNITY’S ARTWORKS

For inspiration, we gave our audiences the following prompts - why don’t you try your own?

¡Censored Voices!

Dictatorship in Chile meant highly restricted access to media and censored news. Additionally, many of those producing protest art did not have access to materials or equipment. In many places around the world, people still face these issues. When we consider access to social media nowadays, our understanding of limited resources is quite different to 1970s Chile, it can be hard to imagine!

How would you tell your story without social media? Think about creating something with limited resources.

¿Art or Necessity?

For many, protest art does not come from a wish to be creative but instead from an urgency to fight against opressors. In Chile in the 1970s, many pieces of protest art emerged after friends or family had gone missing. This sense of immediate threat was at the heart of protest art.

What feels most urgent to you? Think about the message that you most want to share with others.

¡Simplicity!

Many of those creating protest art had no artistic training and were creating messages for people who may not have been able to read or write. Posters needed to share meaning through images and often artists were inspired by the world around them, using imagery of birds, mountains and the sun. It would not have been possible to use words such as 'revolution' or 'resistance' in posters given the strict rules of the dictatorship so artists had to be careful when communicating their ideas.

How would you depict your message without words? Think about using imagery from the world around you.

Transnational Solidarity in Generations

Images courtesy of Kevin Hayes

In 1976, a mural was painted here at the University of Leeds by a group of Chilean exiles, who had left their home in the midst of a cruel and violent military dictatorship. The mural was a copy of one in Santiago, which was eventually destroyed. Over the years, the mural became damaged and hidden – but in 2019, after a student recognised the work, the mural was restored. In fact, it is not far from where our exhibition was held in the Leeds University Union building. You can find it just to the left of the the helpdesk at the entrance, room GR.22

You can read more about solidarity in Leeds here.

Also in 2019, the mural was recreated as a cloth banner at the annual Victor Jara Festival in Machynlleth, Wales. This project was made possible by Mogs Russell and Tim Hollins, who arranged an outline of the Leeds mural to be projected onto the cloth, while visitors came and painted it over the course of a weekend.

You can learn more about the festival here.

The images here were taken by Kevin Hayes, a documentary photographer whose work focuses on labour and social movement struggles, community campaigns, cultural celebrations and world music performers. In one of the photographs, we see Tatiana Hernandez-De Ceapog and her son, Luca, who travelled to the festival to contribute to the painting. On the phone, we see Tatiana’s father, Gilberto Hernandez, one of the original painters of the mural at Leeds. Unable to make it in person, he joined via video call.

You can see more of Kevin’s photography here.

SOBERANIA/SOVEREIGNTY

by jiaying qian

This pamphlet is published by Ecuador’s Ministry of Natural Resources and is about the foundations of the struggle for national sovereignty.

The pamphlet cover is made up of two contrasting colours of black and red. The red circle in the background adds movement to this still image, as if ‘soberania’, meaning ‘sovereignty’, is erupting from the centre with such force that is enough to break the chain.

What is the red circle? Perhaps an oil well.

Petroleum is Ecuador’s largest economic pillar. Ecuador did not seriously begin oil production and large-scale exports until 1972. The previous two economic growth phases were dominated by agricultural exports: the cocoa boom between 1860 and 1920, and the banana boom between 1943 and 1965. If the chain in the image is regarded as a symbol of the solid guarantee of Ecuadorian economic development, then before 1972, it was cocoa and bananas. After 1972, under the auspices of Gustavo Jarrin Ampudia, Ecuador’s Minister of Natural Resources, petroleum took over the place of cocoa and bananas in the development of the Ecuadorian economy. The huge economic benefits brought by petroleum exports, as well as the international prestige gained after Ecuador joined the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), have become a solid guarantee for the new military government to take control of the national sovereignty through the implementation of nationalist petroleum policies.

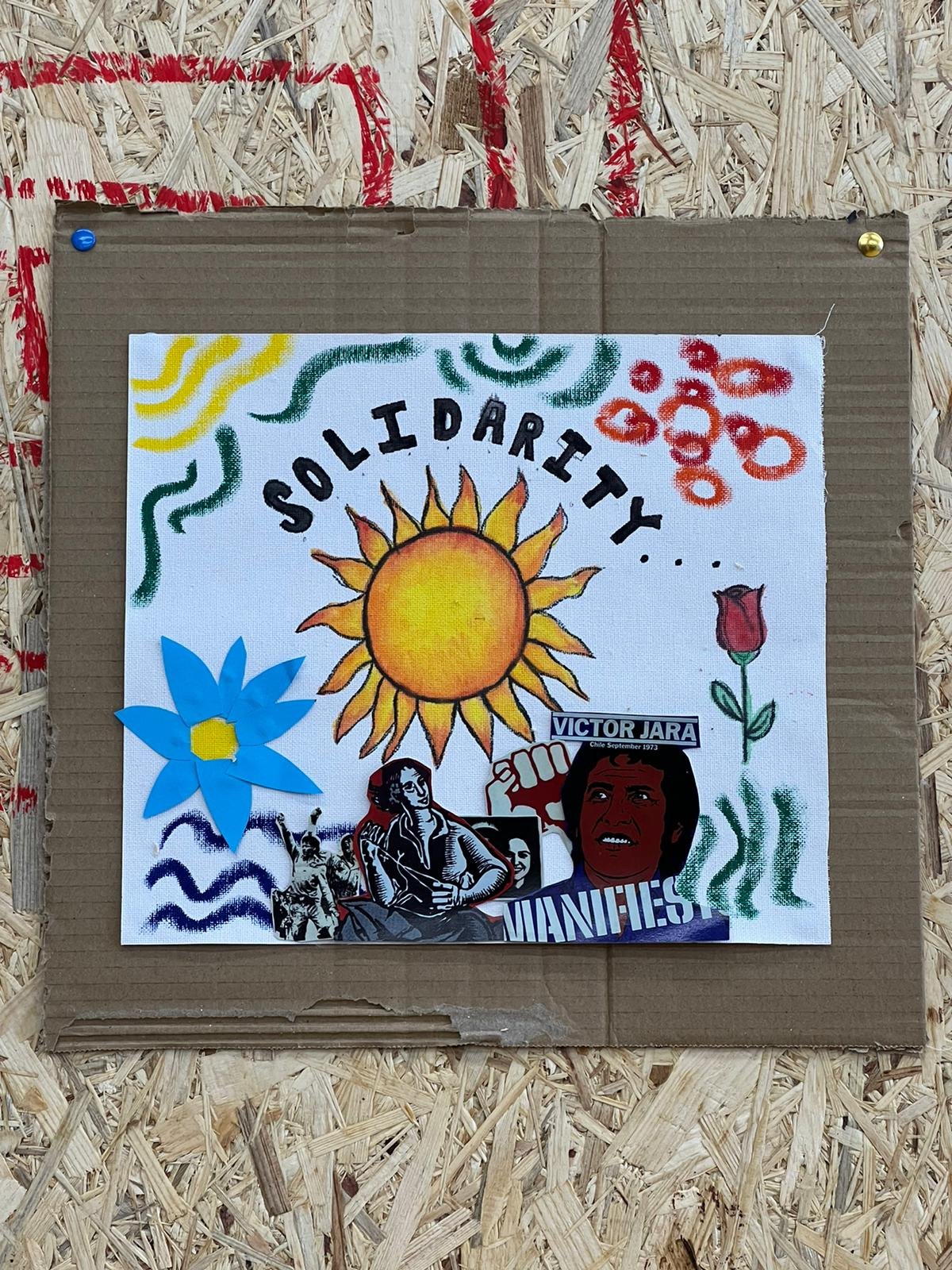

solidarity

by esme mcgowan

This year, the UK experienced a scale and quantity of strikes that have not been witnessed in decades. The recent surge is a collective rising-up of workers against poor wages, poor conditions, and poor management. Many people have hailed ongoing economic crises, or the coronavirus pandemic as causes for industrial action, however, while these more proximate causes are relevant, it is clear that a lot of what workers are fighting for has been at breaking point for at least the last ten years. Our political and economic system increasingly resembles a decayed bridge, creaking and splintering under the mounting pressure of more and more people. Everyday people are overworked and underpaid, in the face of silence, apathy and callousness from those with those who are supposed to be looking out for them.

I have found these strikes deeply moving, watching people of all backgrounds, all careers - nurses, teachers, rail workers, firefighters, tube drivers - standing up together for a mutual cause. This collectivism is what makes us strong, it is what makes movements successful, and it is what gives workers the courage to keep going in a situation of no pay and no say. Witnessing this feels like something rare. As a young person, I don’t have any personal memories of the Miners’ Strikes of the 1980s, nor the global solidarity movements of the 1970s. I can’t begin to imagine what those moments felt like and have no way of truly understanding them.

But as I stood in front of the Popular Music Archive at the University of Liverpool, I caught a glimpse. A glimpse of something that made me feel so proud of, so cared for, and so supported by a particular community of strikers from long in the past: British trade unionists. What I discovered in the archive were unions from the United Kingdom sending solidarity and well wishes to the people of Chile – a country halfway across the world, with a different language, a different culture, a different history, in other words, seemingly entirely disconnected lives. It didn’t seem to make sense. And yet, there it was, in the magazines in front of me: messages of support from the Iron and Steel Trades Confederation, the Fire Brigades’ Union, the Tobacco Workers’ Union, the Transport and General Workers’ Union. All sending solidarity in the fight against oppression and fascism as part of a global union of workers. Despite the fact that Chileans were experiencing this oppression more directly, in the form of a military-authoritarian regime of state terror, British unionists saw this as a common struggle, shared by all. Such international support gave hope to the resistance movement in Chile, making them feel seen and giving them the strength of knowing that what they stood up for was right. Union solidarity also provided practical support, sending resources, assisting exiles, and leading awareness campaigns overseas. In some cases, the support was so strong that workers had a direct impact in the fight. For example, workers in a Rolls Royce factory in Scotland tampered with Chilean military jets so they could not be used. These actions are incredible, and the assistance provided to people thousands of miles away is commendable.

It reminds me that solidarity is not a noun, it is a verb. A thing done, a message sent, a hand held. Solidarity is the understanding that, although we may be facing entirely different circumstances, we are all in this together. In this, we are not isolated from each other, despite linguistic, cultural or geographical barriers, and who's to say that we won’t be next in line to face these struggles. Although the current situation in the UK is different to that of 1970s Chile, the fight for workers’ rights remains. The ongoing struggle for better pay is a symbol of support to groups across the globe that our fight is one - the people are joined together as workers fighting the worldwide capitalist system, and by reflecting on the solidarity of the past, we can learn very important lessons about freedom and struggle moving forward. These messages of solidarity remind me that no one is an island. It is difficult to fight oppression without others, not only through the moral and practical support that makes us stronger, but in terms of rest and assurance of help from others when times get tough. This fight requires people who are hopeful and believe the world can be a better place, but I truly believe this requires us to provide rest and nourishment to those fighting oppression, in the words of Audre Lorde, remember that ‘joy is an act of resistance’. The struggle against oppression is a love letter to community, to mutual aid, to looking after those who need it. As politics in the UK continues to be fraught and polarising, I have found looking inside the box incredibly inspiring. This global community is possible; it has existed before. Reopening artefacts of solidarity from the past has reminded me of this, and with this new understanding I find myself asking: what's stopping us from uniting again?

El pueblo, unido, jamás será vencido.

Below, a recreation of two pages of a pamphlet from the Popular Music Archive at the University of Liverpool.

MANIFIESTO

Image courtesy of the Popular Music Archive at the University of Liverpool

MAYU TANIGUCHI

Over the past six months of studying abroad in the UK, I have experienced several cultural shocks, and without a doubt, one of the most memorable has been the industrial strike action taking place in the UK over the past year. Employees that do not hesitate to withdraw their labour are firmly united by a common goal (wages or gender equality, for example) and are making collective demands. What struck me the most was that participants protested in an optimistic, cheerful atmosphere - some sang with instruments while others danced. This experience changed my perception of “protest”, where I imagined people assembling placards and marching in a depressing manner. A month went by before this particular cultural shock made sense to me. I realised that the relationship between music performance and “optimistic protest” was not unique to current-day Britain, but that it had previously existed in Chile in the 1970s.

Who is Victor Jara?

Victor Jara was born on 23 September 1932, in a small village to the south ofSantiago, to a peasant family. It was his mother, Amanda, who taught him Chilean folk songs while she played the guitar and sang. Victor had a set of exceptional talents, having learned to play the piano and guitar, and became a theatre director and composer in Santiago. He also became a singer and a member of the Nueva Canción Chilena movement (The New Chilean Song Movement). He started to devote himself to the creation of democratic Chile as a socialist folk singer. One of his biographies cites Victor’s words as follows:

“Ever since I was born I have seen injustice, poverty and social misery in my country. I believe it is for this reason that I felt the need to sing for the people. I firmly believe that man must become free during the course of his life and that he must work for justice.”

For people in Chile, Victor was the leading folk singer of the movement and the key figure who continued to stand up with and for the people of Chile.

What is “Manifesto”?

“Manifiesto” is often regarded as one of Victor Jara’s masterpieces. It was the last song Victor worked on before his death, brought about by the military coup led by General Pinochet on 11th September, 1973. This piece is indeed a representation of Victor Jara himself- his persistent will, tenderness and modest dedication to be on the side of the people of Chile as projected in one of the lines of lyrics (English translation):

“I don’t sing for the love of singing or to show off my voice, I sing because my guitar has both feeling and reason…My guitar is not for killers greedy for money and power but for the people who labour so that the future may flower.”

“Manifiesto” is also the name of the re-released album, which contains his works recorded between 1968 to 1973. The re-release was intended to coincide with a fund-raising concert for the Jara Foundation in Chile and went on sale just weeks before Pinochet was arrested in Britain.

Story Behind “Manifiesto”

Victor Jara wrote “Manifiesto” just before Pinochet came into power. Jara was rushed to finish this piece because he anticipated persecution - it was clear that the government of Salvador Allende, Latin America’s first democratically elected socialist leader, was facing significant opposition from the military forces.

Victor Jara’s fate was due to the fact that he had become a politically influential folk singer, closely engaging with the New Chilean Song Movement at that time. This worldwide movement originated in the early 1960s, founded in Chile and Latin America and was defined by Victor as “popular” in the true sense of the term, “of the people”. The movement was intended to call for social justice, including people’s freedom from state oppression and labour exploitation.

If you look closer at the lyrics of “Manifesto,” you may wonder who “Violeta” is, a woman’s name Victor mentions in Manifiesto. According to Victor, Violeta Parra was like a “star which will never be extinguished,” who played a vital role in the movement as a composer. Violeta travelled across the country, saw people’s lives and spent time living with peasants, fishermen and Mapuche Indians. Her deep understanding of working-class people, acquired over 20 years of detailed observation, enabled her songs to reflect the reality of the people and their suffering. The whole social movement was not just a passing trend: it was a reflection of voices from suffering people and the insistent demand for social change.

Influence of Victor’s Piece on Politics and People?

Having served as a socialist folk singer was life-threatening once the military coup took hold. Just a day after the coup that deposed Salvador Allende, Victor was arrested and imprisoned in the Chilean National Stadium alongside thousands of other protestors, where he was severely tortured and murdered. Despite his terrible injuries, Victor boldly sang “Venceremos!” (English translation: We shall overcome) as he was killed. He died on 16th September 1973, five days after the former President Salvador Allende.

Three years after Victor’s death, his music was still prohibited under Pinochet’s regime. His dictatorship, with military force, imposed economic depression, chronic poverty and nepotism. People were forcibly taken by police at night and disappeared. Pinochet also made it explicit that there would be no election in his and his successor’s regime. During the military rule under Pinochet, Chile was anything but democratic.

Despite Victor’s tragic death and the authoritarian regime that followed, people remained strongly united and many groups continued searching for ways to combat and survive the fascist government. People kept protesting for their wages, for the freedom of trade unions and the liberation of illegally imprisoned protestors. Although Victor was silenced, his passion for democratisation, courage to resist illegitimate authority and love for his own country were indeed passed onto people and served as solidarity among people. His songs are indeed still alive today.

CENTRO CULTURAL TALLERSOL

Centro Cultural Tallersol

Chosen by the Team

The Cultural Centre Tallersol was founded in 1977 in Santiago de Chile by a collective of artists and activists who used culture and politics to resist military repression by creating a space for creativity and artistic experimentation under the 1973-1990 dictatorship of Pinochet. During this time, they produced around thousands of posters, pamphlets, and other documents for human rights organisations, as well as political, social and cultural organsiations. To this day, the role of graphic art in networks of countercultural resistance during the dictatorship is little known and studied (translated from UCLA’s summary).

As part of Thinking Inside the Box: 1973, we have been working with one of the founders and current director of Tallersol, Antonio Kadima who is an activist and artist. His artworks and practices have inspired us in the project by providing artistic inspiration. We have tried to do Kadima justice by reawakening the power of his political artworks and sharing with others the visual symbols and techniques we learned from him.

Our project logo draws directly from Kadima’s artworks.

Below you’ll see some examples of some of the posters

we were looking at when we designed the logo.

Can you see the visual symbols and styles we were inspired by?

Speaking to Antonio Kadima also inspired students to think about the motivations, limitations, and urgency of creating political artworks. Kadima himself had been driven by urgent causes - such as spreading awareness of disappeared persons. He was often limited in terms of resources, but also in terms of censorship, and had experience working with and guiding others who did not have the artistic training and background that he did. Students thought through the practical implications of all of this, deciding to provide prompts for participants (What is urgent to you? How would you communicate your message if you couldn’t use words?) as well as providing visual elements and symbols taken from Kadima’s posters for visitors to rearrange in new ways. You can read more about our workshops here.

It is also relevant that Kadima is himself an archivist. Through Kadima, Tallersol has amalgamated a vast collection of posters, leaflets, bulletins, and other printed matter - over 8000 items. While he has contributed significantly to the construction of memory around state terror in Chile, Kadima’s personal mission is rather to preserve, promote, and raise the profile of the anti-Pinochet resistance movement. In this way, Kadima’s work speaks specifically to our them of Hope, Struggle, and Solidarity. Tallersol, like many other archives of resistance, is currently under threat of closure - it risks being assimilated into a societal oblivion driven by gentrification. This is why a project has been set up to begin the work of cataloguing and digitising the collection, to democratise access for the public and researchers.

The selection of posters here are just a few of the 150 Tallersol artworks that have recently been digitised as part of a project between the University of Leeds and the University of California. You can see the collection here:

https://digital.library.ucla.edu/catalog/ark:/21198/z1cz7hzc

‘Chile Lucha’ por todo el mundo/Chile Fights from across the world: How Chilean resistance to dictatorship became international.

Image courtesy of the Popular Music Archive at the University of Liverpool

by Elisa Martinez Relano

The Chile Lucha album represents a story in two halves, told through the protest songs of a musician and the paintings of a visual artist. Released in 1975, it is a response to the violent coup d’état carried out by the army under General Augusto Pinochet two years earlier. The first question that arises when seeing this album, even after a momentary glance, is: why do the translations into Swedish and Finnish feature so prominently? What connects Chile and the Nordic states despite being over 13,000 kilometres apart from one another?

The writer of these songs is Francisco Roca, otherwise known as Luis Veloz Roca. A Chilean folk musician based in Sweden since the early 1970s, Roca’s dual national identity is indicative of the international dimensions of the Chilean solidarity movement. Despite living abroad, he joined various bands that incorporated Andean instruments, resulting in his use of guitars (charango lute and Spanish), flutes (quena and zampoña), and the bombo drum in the Chile Lucha album. This grounds Roca’s musical work in Chilean culture and keeps the listener aware of the political context throughout. Accordingly, printed on the lyrics sheet is a significant declaration that all royalties were to be given to the Chilean resistance movement. Directly named in the acknowledgments of the album are two of the solidarity campaigns that supported the project. First, is the French Comité de Soutien a la Lutte Révolutionnaire du Peuple Chilien (Committee to Support the Revolutionary Struggle of the Chilean People). As one of many bodies formed in France to support the revolutionary struggle after the coup, they sponsored lawyers who went to represent incarcerated Chileans. This committee may also have been the connection to the Chilean artist that created the album cover, Pedro Uhart, who was based in Paris. The second acknowledgement is to Chile-kommittén i Sverige (Chile Committee in Sweden), which was a group that despite being initially populated by the considerable number of refugees arriving from Chile, quickly achieved a majority native Swedish membership. They appear to have advocated for an international line in all activities by collaborating with Stockholm-based campaigns for freedom in Vietnam, Palestine, and Angola alongside Chile (fn1). This is evidence that the movement in Chile, Sweden, Finland, and France contextualised itself within a broader struggle across multiple continents (perhaps a Tricontinental approach). It is this transnationalism that becomes central to the understanding of Roca’s Chile Lucha as a record of hope, struggle, and solidarity.

Not only does the title translate to ‘Chile Fights’, but the photographs of protesters on the inner sleeves and inserts embed an overwhelming sense of active protest into this album. When opening the cover sleeve of the album, the viewer is confronted with crowds holding placards such as ‘La revolución se hace luchando, no llorando’ (The revolution is made by fighting, not by crying). This may also be a reference to the fact that, for some people in Chile, the way they grieved the murders and disappearances caused by the regime was through action and cultural intervention. When we interviewed the graphic artist and founder of the Tallersol Archive Antonio Kadima about his experiences of the period, he also expressed this sentiment pertaining to art as an outlet or reaction to events as they occurred. On the reverse cover, we see a wall plastered with posters and handwritten messages from the far-left organisation MIR (Revolutionary Left Movement). This is a more literal reference to the types of armed opposition operating in the country up to that point. The MIR was founded in 1965 from various socialist, anarchist, and Marxist-Leninist revolutionary factions whose tactics ranged from political pressure to paramilitary action. After the coup they were heavily persecuted on account of being the foremost guerrilla movement. Alongside the lyrics and translations is a quote from the assassinated MIR leader Miguel Enríquez ‘La lucha será larga y difícil […] hasta vencer’ (the fight will be long and hard until defeat). But whose defeat? Enríquez’s combined melancholic and hopeful tone denotes the duality of struggle, as he contemplates what he sees as the inevitable loss of life against the opposition’s eventual demise. Roca echoes this in the song ‘Palomita-Palomita’, which alludes to the particularities of the Chilean context. Together with Pinochet’s oppressive censorship, the fact that Chile spans over 4,000 kilometres from north to south meant communication could be difficult. Therefore, the song describes ‘palomita mensajera’ (messenger dove) who must resist her wings being cut so that she can fly to inform people of current events (fn2). The dove serves as a triple symbol: for freedom, for communication, and for the natural landscape of the country. This offers an explanation of why birds are such frequent motifs in the protest posters of the period, acting as a signal to the population that the art pieces on which they appeared concealed important communication. Thus, even from beyond Chile, Roca reminds both Pinochet and the wider world that the population would not give up fighting for freedom.

Beyond the music itself, the album artwork provides further insight into the cultural production of Chileans living abroad as well as other global solidarity efforts. The illustration on the vinyl cover was adapted from a painting by Pedro Uhart, who, much like Roca, was born in Chile and moved abroad before the coup. Instead of Sweden, he settled in France. The original piece was one of his ‘floating murals’ painted during September 1973, only weeks after the Allende government was overthrown. Without enough money to buy a canvas, in 1972 he began using old sheets which he could hang in the street like the murals found in Chile. By adopting this medium, he built upon the Latin American tradition of mural painting. In turn, a reclamation of public space could take place in which Uhart increased the visibility of his politically charged artwork. On the 25th of September 1973, 14 days after the coup, Le Monde described it as the Chilean Guernica, in reference to Picasso’s depiction of the human experience of terror, during a review of the Paris Biennale (fn3). Uhart also displayed the work across the European continent, for example in Warsaw, Poland. However, looking further into the history of this painting serves also to mitigate this hopefulness associated with a transnational solidarity movement. The original piece and Pedro’s subsequent work were subject to censorship by the leaders of French art organisations who did not agree with his overtly political tone. Perhaps this is another reason why the mural worked so well as a medium for Uhart; he could take advantage of the ‘outdoor’ and ‘unofficial’ nature of these spaces to raise awareness for Chile in a way that he could not elsewhere.

Present in Uhart’s artwork is the style of graphic design found in typical Chilean 20th century posters and cartoons, blended with features of the storytelling tradition and folkloric art practices of his upbringing to create a hybrid Chilean design. The resulting composition has little unfilled space, instead being covered with distinct elements and bright colouring. Such an approach makes the blank section in the top left-hand corner of the mural even more striking, as only a single eye flowing with tears occupies the area. This emptiness locks your gaze onto the section, almost becoming a visualisation of the chasm left by the thousands of people that would end up being displaced from their families over the duration of the dictatorship. Thousands were imprisoned, murdered, or exiled. This largely figurative piece depicts US soldiers standing on top of a Chilean flag, as it is being strangled by the heavy ropes that the artist has woven through the painted sheet. This lays out Uhart’s accusation against countries such as the USA for facilitating and later upholding the Chilean coup and military regime. Finally, a sea of people split into waves of red, white, and blue are rising up from the bottom of the mural. These figures carry hammers and g

uns, or, the implements of manual labour and armed resistance. Roca and Uhart’s messages converge at this point, displaying the determination of the Chilean people against oppression. As such, this part of the painting is what appears on Roca’s album cover. Yet on the album’s modified version of the painting, it has been rotated in a way that the waves of people now appear to form the shape of Chile’s coastline. This impression is maintained as the names of key cities in the struggle of the coup (Santiago, Valparaiso, and Concepción) have been added to the drawing.

For people hoping to learn from the experiences of this period in Latin America, ‘Chile Lucha’ provides a window into this historical context. The artwork provides insight into the roles of key nations and organisations involved in solidarity activism, as well as the challenges they faced. The multiple stories, people, and artforms combined within this one piece is a testament to the collaborative nature of resistance movements linked to the Chilean cause.

Footnote 1: Charlotte Tornbjer, ‘Moral shock and solidarity. 1973 and the Swedish commitment to Chile’, in 1973: a meeting with the spirit of the times, ed. by Marie Cronqvist, Lina Sturfelt, and Martin Wiklund (Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2008) pp. 56-70 (p. 63).

Footnote 2: ‘Conversando con Francisco Roca’, Perspectivas a través de la Nueva Canción Chilena, University of Chile Radio, 23 October 2013 <https://www.mixcloud.com/borisenaud/perspectivas-40-ruch-02/>

Footnote 3: ‘Publications’, Pedro Uhart <https://www.pedro-uhart.com/WebPagesFR/presse.php>

London N7 7QG

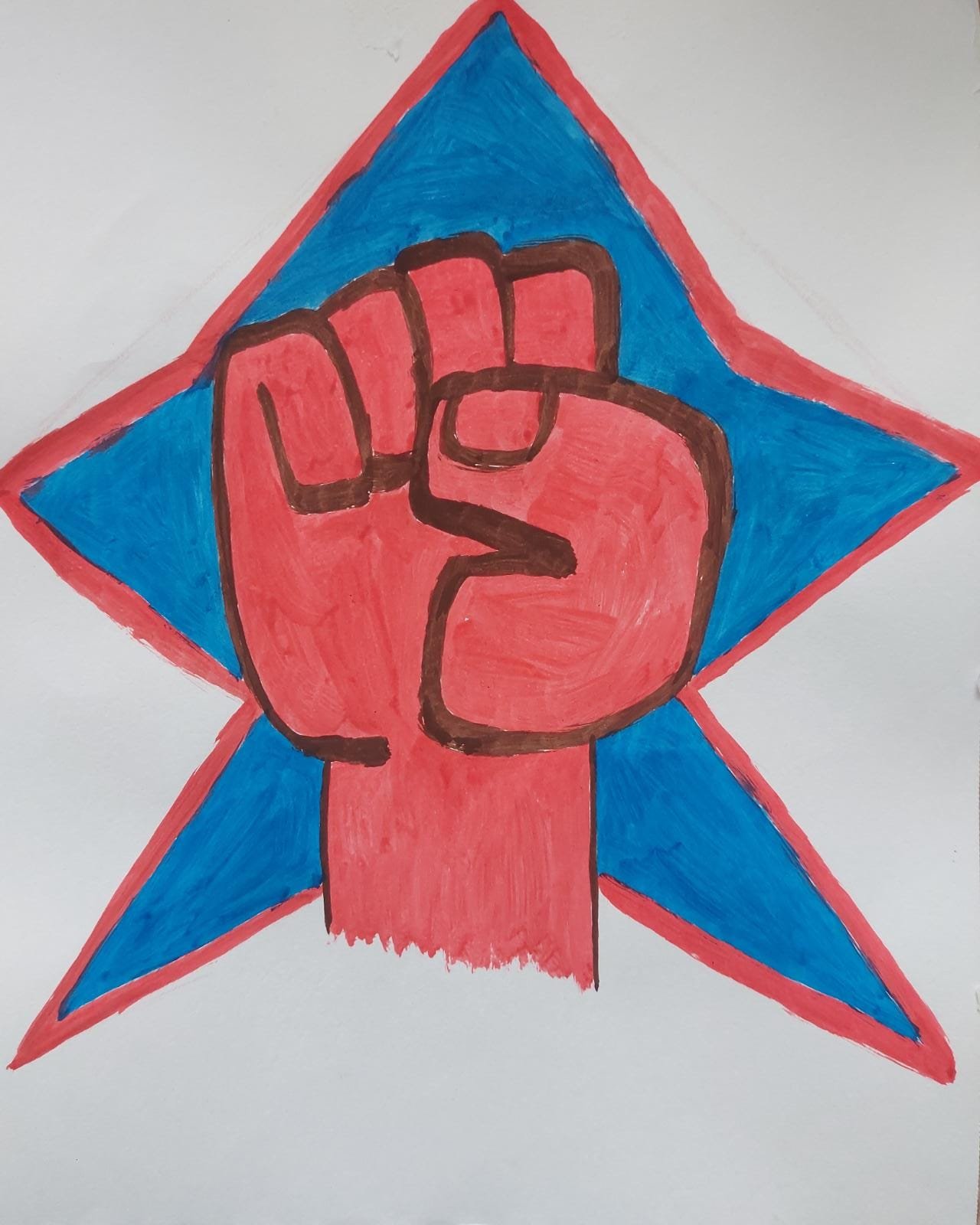

Senate House Library Latin American Political Pamphlets Collection

by jiaying qian

This is a poster from the Chile Solidarity Campaign (CSC).

The first sight of it may remind you of the flag of Chile. Blue, white, red, and a five-pointed star guiding the way to progress and honour. However, unlike the national flag, the colours on this tightly clenched right fist are not evenly split between blue with white and red. Visually, the red palm and wrist are significantly larger than the five curled fingers in blue and white, so when your eyes fall on this poster, you are drawn immediately to the large red area in the centre of the page. This distribution of colour reveals what the CSC wants the audience to focus on: this vast expanse of red alludes to the blood shed by Chileans for democracy and human rights, spilling into the message that Chileans urgently need more support for their struggle.

The CSC was established in 1973 and closed in 1991. In September 1973, the Popular Unity Government led by President Salvador Allende was overthrown by a military coup backed by the CIA and foreign corporations, and Chile was then plunged into 17 years of dictatorship, led by General Augusto Pinochet. During Pinochet’s regime, human rights and democracy in Chile regressed dramatically, with thousands of Chileans killed by state terrorism and hundreds of thousands more forced into exile as they fled or were deported. In the course of Pinochet’s neoliberal economic reforms, the rapid economic growth achieved in Chile was accompanied by a sharp rise in unemployment and a great impoverishment of the working classes, as well as the marginalisation of groups such as peasants and indigenous peoples.

In 1974, in a pamphlet produced by the CSC, Ron Hayward, the general secretary of the British Labour Party at that time, stated that ‘people in Britain must realise that what happened in Chile in September 1973 not only affected Chileans - it struck a blow at democracy throughout the world’. The CSC was therefore set up in Britain with the aim of influencing British Government policy towards the junta in Chile and calling for more support from the British public. The CSC’s solidarity campaigns were conducted in two main ways. One was to isolate the junta by persuading the British Government to halt all arms supplies, break off diplomatic relations, and end trade with Chile. The second was to raise funds for the resistance movements in Chile, mainly targeting the assistance to trade unionists, peasants, students, and the civil society.

Through the CSC’s campaigns in Britain, the struggles of Chileans under the junta dictatorship received more attention and their solidarity movements for democracy gained more support. It was not until President Patricio Aylwin came to power in the 1990 free elections and ended Pinochet’s 17-year dictatorship that democracy was finally restored in Chile, and the CSC ceased its activities. Even 50 years on, these visual symbols hold a powerful and timely message. Although the CSC closed in 1991, such a visually striking poster gives us hope; it reminds us of the power of solidarity and honours those who struggled in this particular campaign.

Por una universidad libre de la presencia imperialista

Senate House Library Latin American Political Pamphlet Collection

BY ROSA DE KORTE

Por una universidad libre de la presencia imperialista

For a university free from imperialist presence

Death to the oppressive regime of imperialist education! – that seems to be the central message transmitted from this political poster distributed by the Organización Continental Latinoamericana y Caribeña de Estudiantes // Continental Latin American and Caribbean Student Organization (OCLAE).

Still active today and followable on Instagram (@oclae_oficial), OCLAE was formed in 1966 and is at its roots a platform for student voices. Put simply, OCLAE are defenders of – and advocates for – freedom and democracy in education. Increasing literacy rates and access to free education, decolonising curriculums and hierarchies, as well as establishing a foundation of solidarity between autonomous student bodies are some of the ways they work indefinitely towards these goals.

Likely produced in late-sixties Cuba, where the OCLAE was originally founded, this poster visually represents their mission, honing in on the student-led effort to eradicate imperialism from Latin American curriculums. Against a red evocative of communist iconography sits what appears to be a book, which is propped open to resemble a half-open coffin. Inside the book, there is an apple which has the United State’s flag planted in it. The significance of the flag can be easily deduced as the ‘presencia imperialista’ (‘imperialist presence’), and may even remind you of the moon landing. But what should we make of the apple?

Perhaps you are familiar with the old American phrase “apple polisher”, referring to someone who bootlicks their superior, usually a teacher. This was primarily used between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries along the American Frontier, where students and their parents would gift (often live-in) teachers an apple as payment for their hard work. Symbolically, we can also trace the biblical associations of the apple back to the fruit of knowledge, originating from creation stories of Adam and Eve. Fidel Castro, leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, maintained Cuba as an atheist state throughout his years in power, weakening the Vatican’s influence in the country. So, it is certainly not far-fetched to consider this icon as a nod to not only imperialist forces, as explicitly stated, but with it, religious ones too.

Now think about how the string is trailing off towards the viewer. These posters would have likely been put up across Latin American and Caribbean countries through national members of OCLAE, who would have displayed them in universities, street corners, and other public spaces. State-sponsored posters were distinct in style and often had the function of educating the masses. They did this through visual media as well as short, ideologically fused taglines, to communicate the 1959’s founding revolutionary goals, such as eradicating illiteracy in the country. So, if the viewer were to pull the string, the coffin would fall shut, trapping the imperialist fruit of knowledge inside and closing this chapter of US influence in Latin American education systems. This implication of the viewer empowers them in their struggles towards independence.

Reading so deeply into the symbols may not be imperative but the poster undoubtedly has a general sense of immediacy, inviting viewer participation. What remains in this archival material is a lingering feeling of struggle against structures that can and must be challenged by those it fails to serve.

I am certain that you, a participant of our exhibition, have been affected in some way, shape, or form by the wave of industrial strike action in recent months and years here in the UK. In this context, the poster’s ability to empower everyday struggles and the peoples’ ability to shape their future becomes increasingly relevant. In looking at the multitudes of ways in which Latin American student bodies collectivised this struggle for change in the past, we can uncover ideas, both big and small, with the potential to inspire us in the present.

¿Why Leeds?

BY Elisa Martinez Relano

2023 serves a dual significance. Not only is this the 50th anniversary of the 1973 coup d’état in Chile, a year during which many other Latin American countries were under authoritarian regimes, but 2023 is also Leeds’ Year of Culture, where the culture of those who live and have lived in this city are being celebrated. Leeds City Council Museums and Galleries, for example, have curated exhibitions such as ‘Overlooked’ and ‘Leeds Artists Show’ to tell the story of Leeds through the people who lived here. So, as the location for the annual exhibition project Thinking Inside the Box, Leeds is a very relevant location.

Yet, you may find yourself asking, what is it that links our city to the people affected by a military dictatorship in Latin America half a century ago? The fact is that the history of Chile played a part in the local history of Leeds, but also in that of the University of Leeds itself.

In 1976, a mural was painted within Leeds University Union by exiled activists and Chilean students. These individuals had found themselves in Leeds after leaving behind the right-wing dictatorship that had taken power in their homeland of Chile. General Augusto Pinochet had mobilised the armed forces to overthrow the democratically elected government of the Socialist leader Salvador Allende, and over the following years, opposition to the regime was silenced through disappearances, assassinations, imprisonment, and forced exile.

The mural eventually fell into disrepair after the decision to construct a wall covering the artwork, which resulted in it being hidden from view during the following decades. As a consequence, the painting and its message had been essentially forgotten (or silenced) until its rediscovery during building renovations in 2017. It was only when a Chilean student at the time recognized remnants of the Chilean national flag that an effort was made to identify the origins of the artwork. A restoration project was initiated to replace deterioration in the paint and plaster, while master’s students of the University of Leeds’ Art Gallery and Museum Studies programme carried out extensive research into the local Chilean community.

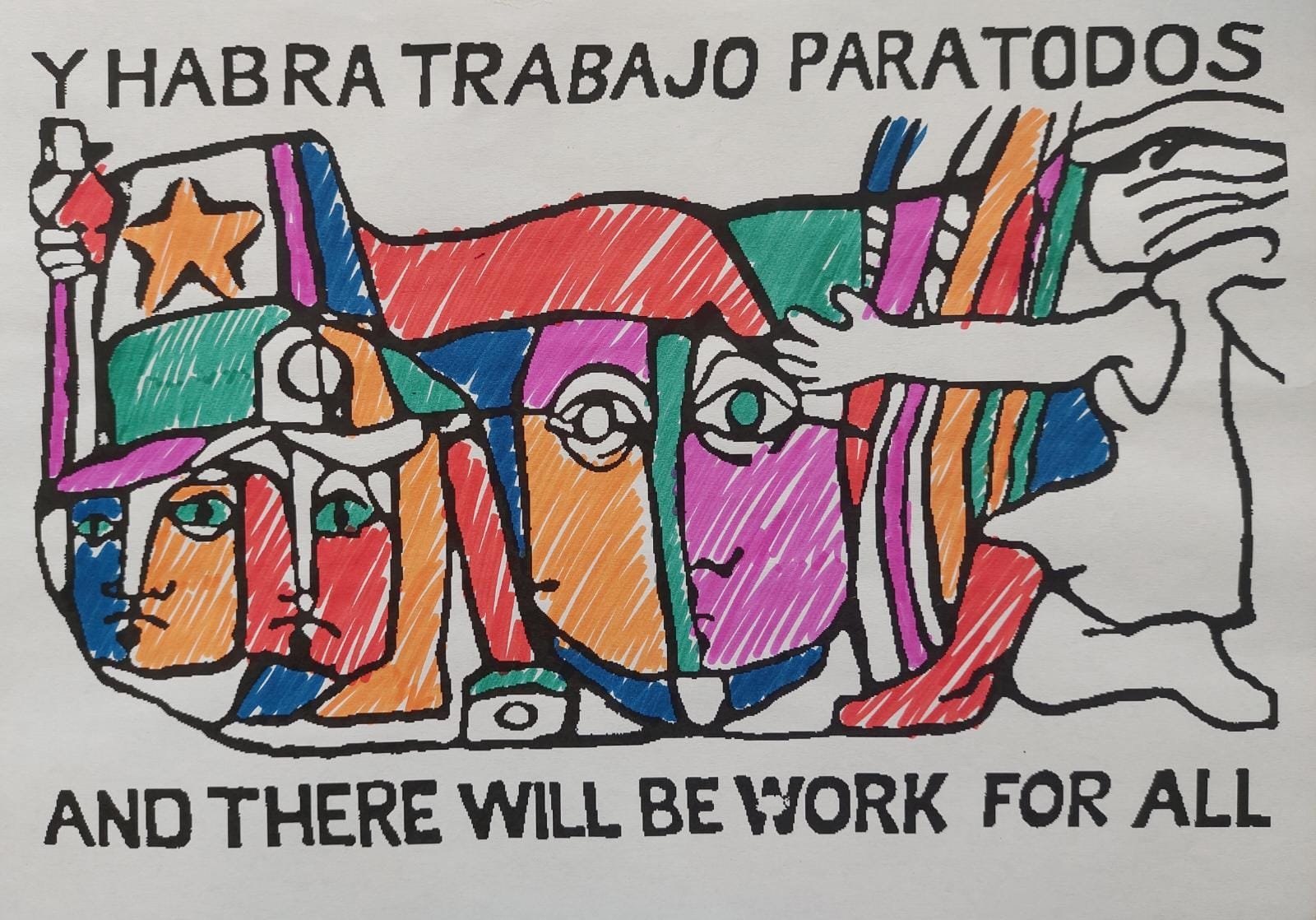

Pedro Fuentes, Rafael Maldonado, Gilberto Hernández, Eduardo Espinosa, and Ricardo Escobar were some of the people who painted the Leeds mural in 1976. Gilberto and Eduardo served over two years in concentration camps or prisons and were only released in exchange for accepting a life of exile in Britain. During interviews conducted by the MA students throughout 2018, they spoke about their experiences as refugees in 1970s Britain. They expressed pride in being refugees, feeling gratitude and strength in their status as exiles and survivors. In particular, they appreciated the solidarity from local communities in Leeds, which is something that seems particularly relevant to the current wave of anti-refugee sentiment in Britain today. They also expressed that ‘the mural is a symbol of memory’, as well as ‘solidarity and friendship’. It was created during a period of concern for those who had stayed behind in Chile, and the central purpose of their involvement was to reinforce solidarity with their fellow citizens in Chile. The senior management staff at their old universities in Chile had been replaced by members of the military command, which is also why the University of Leeds is such an important setting for the mural. The fact that they could express their political preoccupations more freely within an educational organisation here was a positive and reaffirming act of protest itself.

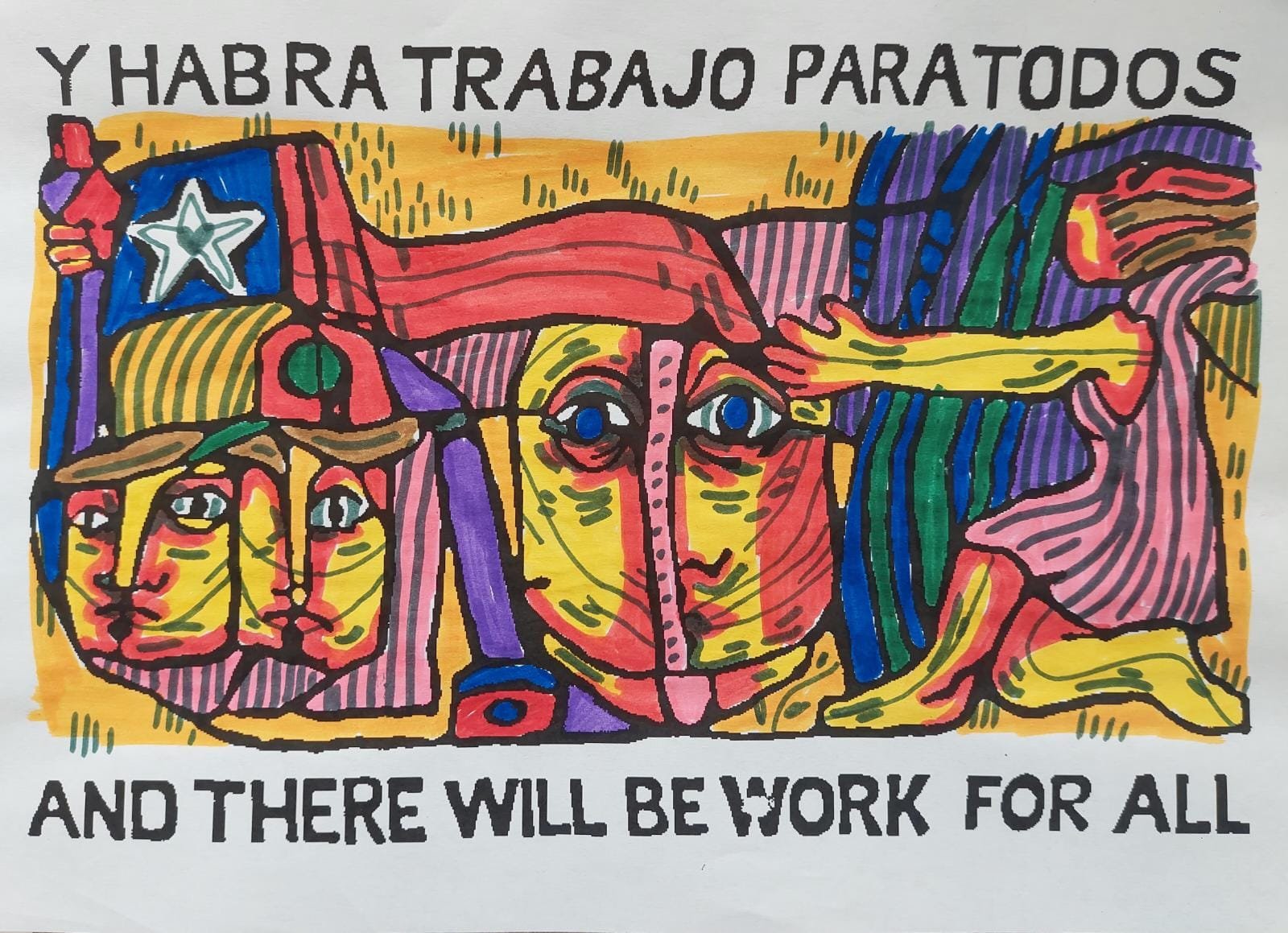

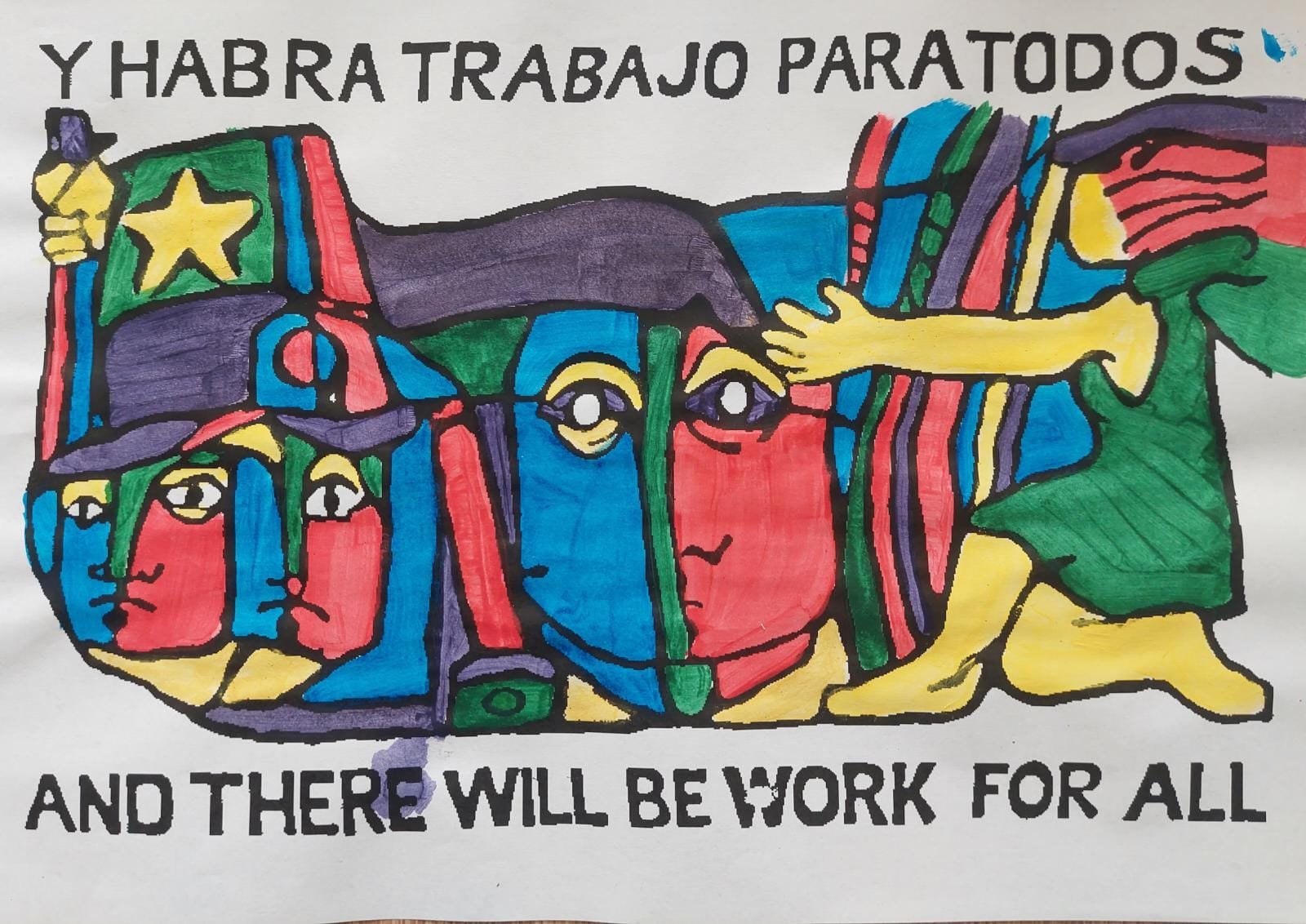

Image of solidarity mural at the Leeds University Union building, from Leeds Art Fund

The artwork is bordered with a slogan in both Spanish and English: ‘...and there will be work for all’. In the centre, four faces of manual labourers (most likely, farmers and miners) are represented alongside a woman grasping a bundle of wheat. Above the scene, the Chilean flag appears to be transposed into the shape of a mountain or factory in the distance, a reflection of hope that nationalisation would put industry back into the hands of the general population and provide a better future for all. This Leeds mural is an exact copy of the Brigada Ramona Parra mural in Chile’s capital city Santiago (fn.1). It formed part of a series of murals outside the Barros Luco Hospital that outlined this hope for nationalisation across mining, agriculture, and industry as well as the demanding happiness and the protection of children. In Chile, and Latin America more broadly, murals have a long history of cultural and political significance, particularly since the Mexican muralist movement of the early 20th century. In the years leading up to Allende’s election, murals played a central role as an informative tool that encouraged the population to engage in politics. It was a time of instability, but there was a belief that positive change was attainable, and murals were an art form that had the ability to reach the masses organically. After the military removed Allende from power, these artworks were covered or destroyed. In this context, the restaging of the mural in Leeds allowed this group of activists to reoccupy the type of spaces that had been taken away from them in Chile. As a result, the Leeds mural is one of the only surviving versions and has since inspired others to restage the work. In 2013, a welsh-language version was painted at El Sueno Existe festival in Machynlleth Wales, and now in 2023 Thinking Inside the Box Leeds will reclaim this history again. Thus, the mural lives on, acting as a living artefact of the Allende-era Chilean struggle.

Cover of Inti-Illimani concert catalogue, 1985, from the Popular Music Archive at the University of Liverpool

This story did not end in 1976. The Chile Solidarity Campaign in Leeds continued to function throughout the late 20th century. The interviews with the Chileans who painted the Leeds mural reveal that many in Yorkshire condemned the dictatorship and advocated for the release of political prisoners in Chile. As part of Thinking Inside the Box: 1973, we visited the Popular Music Archive at the University of Liverpool and discovered yet more evidence of this Leeds-based solidarity. The picture here is of a concert brochure for the 1985 Inti-Illimani UK solidarity tour of London, Leeds, and Edinburgh. It demonstrates how people collaborated and participated culturally in supporting the Chilean people. Inti-Illimani were an Andean-folk-protest music group who were on tour in Europe when the coup occurred, allowing the Pinochet regime to ban them from re-entering their native country of Chile between 1973 and 1988

Image from the Inti-Illimani concert catalogue, 1985, from the Popular Music Archive at the University of Liverpool

This prompted a decades-long tour of the world. Their concert in Leeds on the 6th of October 1985, with the English folk singer Frankie Armstrong as a special guest, positions the city within a broader history of cultural solidarity for Chile. On that day, the traditional harmonies of Latin America and English folk music were played in unity. It is important to note that this was not an isolated event. The concert programme also includes photographs from Chilean solidarity marches held in Leeds, which cements Chile within our city’s culture of protest. In fact, an advert and article in the Leeds Student newspaper from 1980 confirms that Armstrong and Inti-Illimani had already played a charity concert in Leeds Town Hall on 21st November 1980 in protest of how the British government appeared to conceal the atrocities suffered by Chileans. Even the national report of the Chile Solidarity Campaign’s activities noted the fact that 2,000 people, including the Labour MP Derek Fatchett as a speaker, attended Inti-Illimani’s concert in Leeds Town Hall on 7th September 1983. By acknowledging the history that Leeds and the Chile Solidarity campaign share, we as a city are looking towards the past to inform the future.

Footnote 1: The murals form a sentence which reads ‘…Y ahora también Chile, Y se nacionalizarán las minas, Y la tierra para el que la trabaja, y el cobre para los Chilenos, y nace el hombre nuevo, y habrá trabajo para todos, y a prepararte a dirigir la industria, y también habrá alegría, y no habrán angustias para nacer, y los únicos privilegiados los niños’; Alexandra Denisse Reyes Espinoza, ‘Muralismo e imaginario latinoamericano. Análisis comparado de un sentimiento de resistencia latinoamericana, 1910-1973’ (unpublished thesis, University of Valparaíso, 2019) pp. 61-66. <http://repositoriobibliotecas.uv.cl/bitstream/handle/uvscl/3531/Tesis%20Alexandra%20Reyes%20Espinoza%202019.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y>

Canción para matar una culebra/song to kill a snake.

Image courtesy of the Popular Music Archive at the University of Liverpool

by lauren ddin

In September 1970, Salvador Allende, a candidate of the Unidad Popular (Popular Unity) party, was elected President of Chile. Allende was the first Marxist to gain power in a liberal democracy in Latin America, with a campaign that called for a ‘peaceful road to socialism’. However, on September 11th 1973, following months of rising political tensions, Chile’s democratically elected president was overthrown by the head of the armed forces, General Augusto Pinochet. Pinochet proceeded to orchestrate a regime of terror and violence in which repression and torture became institutionalised aspects of society. Under his dictatorship, numerous extra-judicial killings were committed, in particular, many political dissenters, artists, and intellectuals were detained and killed. According to Amnesty International, over 3,000 people are officially recognised as having disappeared or been killed in Chile between 1973 and 1990, while 40,000 were subject to political detention and/or torture. Without a doubt, Chile experienced a cultural blackout produced by the repressive measures of the authoritarian state. Many artists went into exile, either abroad or internally, and continued to create pieces of cultural resistance.

Specifically, the image I have decided to study is a vinyl cover that belongs to the Chilean music group, Inti-Illimani, an instrumental and vocal Latin American folk band. At the moment of the Chilean coup, the band was on tour in Europe and could not return to their country as the military junta of Pinochet had outlawed their music. Consequently, they were forced to live in de facto exile. Inti-Illimani was formed in 1967 by a group of college students, and they quickly gained fame in Chile thanks to a cover of the song ‘Venceremos’ (We shall win), which served as the national anthem of Salvador Allende's Popular Unity party. The vinyl cover I have chosen is from the 1979 album ‘Canción para matar una culebra’ which means song to kill a snake. The album’s title is a reference to a poem titled Sensemayá, by Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén.

The vinyl cover presented speaks directly to ‘Hope, Struggle, and Solidarity’, the overarching theme of our project and exhibition. The diaspora of artists from Chile is clearly represented in the figure of the man seen holding a guitar and suitcase, and yet this sorrowful scene is contrasted with an exuberant use of colour, as well as symbols such as a white bird and mountains to represent hope and solidarity for a better future. But what really caught my eye when I first saw this artwork was the snake, whose body is wrapped around the vinyl cover but whose head is creeping onto the image we see on the front cover. On the back of the sleeve, it becomes clearer that the the snake, which is coloured to evoke the flag of the United States, has wrapped itself around the mountains. To my interpretation, this is a metaphor for the US’ involvement in the fall of the Allende government; the image of the snake wrapping itself around the mountains alludes to the way that hopes for a better future were suffocated. In the name of containing a ‘communist threat’, the US opted to subdue the dream of socialism.

This element of the artwork motivated me to learn more about the CIA's intervention in Chile, which continues to be one of the most controversial topics related to US foreign policy. In fact, The Chile Declassification Initiative, approved by President Bill Clinton, resulted in the declassification of about 24,000 documents between 1999 and 2000. Yet to this day, academics have still been unable to agree as to whether the US was directly behind the 1973 coup. What is known is that the US backed Pinochet’s seizure of power; it is also clear that conditions the CIA covert operations prepared the ground for Allende’s demise. Within the context of the ideological confrontations of the Cold War, scholars agree that the US Secretary of State at the time, Henry Kissinger, considered the leftist government of Allende to constitute a threat to US interests as part of the Soviet Union’s efforts to expand communism. US anxiety was already heightened due to Cuba’s transition to a Communist state. In fact, the US followed a containment policy that sought to keep communism out of the Western hemisphere by subduing the spread of ‘communist ideology’ in a bid to strengthen US imperialism. Overall, academics acknowledge that Kissinger and the containment of communism coupled with President Nixon’s approval played a central role in the US’ involvement in destabilising Chilean politics in the lead-up to the coup. Yet, the increased availability of sources made possible by the declassification of official records has not necessarily given us any conclusive answers; more often, it has served to widen the gaps in the existing body of knowledge by creating new layers of debate/contested history.

Fifty years have now passed since the coup d’état was staged in 1973. Undoubtedly, the shadow of Pinochet's regime remains as Chilean society continues to experience a great deal of pain for the dictatorships’ victims. Similarly, the CIA’s reputation remains tarnished by this incident which continues to be discussed in mainstream media until this day. Even as recently as 2021, declassified documents confirmed Australia worked with the CIA to oust the Allende government. There is clearly a vast deal of knowledge that is left to be uncovered surrounding the events of 1973 in relation to the “facts” - but the surviving collections of posters, vinyl covers, political pamphlets, and music produced during this period offer something different by serving as a window into the lived experiences that the regime sought to repress.

References

Amnesty International. 2013. Chile: 40 years on from Pinochet’s coup, impunity must end. [Online]. [Accessed 01 April 2023]. Available from: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2013/09/chile-years-pinochet-s-coup-impunity-must-end/

Goldberg, P.A. 1975. The politics of the Allende overthrow in Chile. Political Science Quarterly. 90(1), pp.93-116.

Shiraz, Z. 2011. CIA Intervention in Chile and the Fall of the Allende Government in 1973. Journal of American Studies. 45(3), pp.603-613.

Los cambios estructurales en la economía peruana.

Image courtesy of the Senate House Library Latin American Political Pamphlet Collection

by annika dhakad

Los cambios estructurales en la economía peruana.

El fracaso del populismo militar (1968 – 1976)

Structural changes in the Peruvian economy.

The failure of military populism (1968 – 1976)

In Peru, due to the expansion of popular sectors in marginal cities who came from different parts of the country, the political current of populism began in the middle of the 20th century. People sought agrarian reform, industrialization, state planning, and the reduction of social and economic inequality. In 1963, the populist government of Fernando Belaunde came to power, promising to comply with popular demands; however, the government became involved in a series of scandals, while its policy changes allowed the armed forces to carry out a coup d’état in 1968, under the leadership of General Velasco Alvarado.

Velasco's popular military government was marked by processes of profound and radical economic and social reforms. These structural changes occurred in one of the most traditionalist Latin American countries, through the expropriation and nationalization of foreign-owned private companies, mostly North American. The booklet we see here was published by “the “Jose Maria Arguedas” publication: national reality series”, in reference to the famous anthropologist and writer of the same name.

The image on the cover, attributed to C. Brudenius, presents a detailed black and white illustration against a bright red backdrop. We see a crumbling government building on the verge of collapse: this represents the Peruvian economy in a state of decay. Meanwhile, the people of Peru are surrounding the building, working together and making every effort to prevent the complete destruction of their economy. To the side of the building we can see an elderly man representing the United States lurking behind the dilapidated building, wearing his signature pilgrim hat.

Attempt to nationalize a US mining company by a military government in Peru amid agrarian reform and social inequality

Image courtesy of the Senate House Library Latin American Political Pamphlet Collection

by patricia roman

On October 3, 1968, a military coup led by General Juan Velasco Alvarado took place in Peru. Thus began the so-called Revolutionary Government of the Armed Forces, with promises to carry out agrarian reform and close the gaps of social inequality. The government expropriated and expelled the North American International Petroleum Company (IPC). Convinced that the country's natural wealth was being plundered by “Americans”, Velasco also sought to nationalize the Southern Peru Copper Company, but was unable to do so legally.

The illustration on this pamphlet shows the Peruvian military government, representing Velasco and his commanders, on top of an excavator as it carries away Peruvian copper. Also on the excavator, which belongs to Southern Peru Copper, we see a version of the familiar US "Uncle Sam" figure holding up the contract that prevents Velasco from nationalizing the company. Beneath the excavator, to the bottom of the scene, we can see people (peasants and workers) showing their discontent by protesting for agrarian reform and better wages.

The themes of this image clearly relate to the later, more well-known coup that took place in Chile five years later, in 1973. In both cases, the influence of the US is overwhelming and played an important part in maintaining authoritarianism and neoliberalism.

A CORDEL OF SOLIDARITY AND STRUGGLE

mANUELA MARCONDES

In Brasil (mainly the Northeast, or Nordeste), the ‘cordel’, an illustrated pamphlet, was a popular way for important messages to be communicated to a population that had low literacy rates, but who could be reached through their great love for folk music and storytelling. The pamphlets would contain songs like the one we see here, which were written for people to commit to memory and sing in taverns and on the road so that the content of the cordel could be shared with as many as possible.

This cordel, with an illustration by Marcelo Soares, aims to inform the nordestinos of ‘The Law of Two Years’ which gives farmhands two years to collect the money they are owed by landowners (the ‘patrão’, or boss). While the aim of the cordel, to communicate labour laws, is straightforward, a voice of solidarity amongst working people in the Nordeste is heard loud and clear in the folk song. The last two stanzas read:

Image Courtesy of the Senate House Library Latin American Political Pamphlet Collection

Brothers of this same nation,

There so many different laws

That must be made clear by us,

as Brasil won’t leave a trail for us.

Read and sing this tolheto -

Study it with your brother,

Your companion, and your friend.

An organised union is the lifeforce of this nation.

While the woodcut image printed on the front of booklet is credited to Marcel Soares, the song in this cordel is not attributed to one specific author. In this, we learn a wider truth about the nature of cordels and the solidarity they promote amongst a struggling people. The cordel is written with one purpose and one purpose only, to galvanise workers to claim what is rightfully theirs and inspire brotherhood amongst nordestinos. The sense of solidarity here is local, it creates a political subject based on nordestino identity itself; it defines their struggle from the perspective of a largely slave-descended, worker and farmer population living in an area that is prone to drought, dominated by exploitative landowners and bosses, and which has been historically neglected by the central government.

This cordel shows us the solidarity amongst working people and their hope for fair laws and working practices. The cordel gives us an insight into how soliadarity was practiced and communicated, and gives a powerful voice to an underrepresented group whose agency is often overlooked in historical literature. In a quiet way, this simple pamphlet says a lot about the ways in which the working man can stand up to a country limiting their freedoms and stifling their hope.

canto para una semilla

Image Courtesy of the Popular Music Archive at the University of Liverpool

BY BEA OLDING

Canto Para Una Semilla: Song For a Seed

In homage of Violetta Parra and ‘su personalidad creativa’.

Ayer sembró la simiente Yesterday she sewed the seed

que hoy florece y fructifica. that today flourishes and bears fruit.

Epílogo, Violetta Parra - Inti-Illimani

True to her own lyrics, Violetta Parra, a prolific artist of 1960s Chile, planted the seed of the political, social, and musical movement Nueva Canción, nourishing it until her passing in 1967. This album, Canto Para Una Semilla, is a homage to her life, to ‘su personalidad creativa’, her creative personality. Produced four years after her death, composer Luis Advis took inspiration from her poetry collection Décimas – or Stanzas, in English. All the lyrics from the album are taken and rearranged from Décimas.

Nueva Canción was a musical movement that swept across Latin America in the 1960s and ‘70s. Driven by the political impetus for social justice in countries that were experiencing great poverty and inequality, this powerfully political folk music was developed with indigenous instruments from across the continent. Whilst the guitar - so imperative to Latin American folk music- remained central, the use of Andean instruments was also popular, such as the charango, belonging to the lute family, the quena, a flute made from wood or bone, and the zampoña, panpipes.

Born to a poor family and surrounded by music, Violetta Parra took up the baton for change and popularised her concern for social conditions within Chile with her wide knowledge of Chilean folk music. Her most famous song, Gracias a La Vida, is still played often today. Although it was Parra’s musical talent that pioneered Nueva Canción, other musicians around her quickly joined and shaped the future of the movement. The two artists who interpreted Parra’s work on this album (her daughter Isabel Parra and the student-formed band Inti-Illimani) are two of just many who continued to promote and shape Nueva Canción beyond Parra’s early death at the age of 49. From 1973, the year that General Augusto Pinochet led the armed forces to overthrow the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende, both the artists and music of the Nueva Canción movement, as well as the Andean instruments they played, were forbidden by the regime.

Me amarga la situación I am bitter about the situation

cómo cambiarla pudiera. how i could change it.

Pero ordenaré el problema But I will order the problem

al ritmo de una canción. to the rhythm of a song.

La Esperanza, Violeta Parra - Inti Illimani

The art we see here - the vibrant colours, the depiction of the sun and the bird - is indicative of the Latin American folk art that coloured a dark time in Chile. In a time of great suffering and need for faith, it was the art that connected and reconnected loved ones across the long, thin stretch of land that is Chile. This style, full of wonder and magic, was one that I came across time and time again as part of the project; on cassette covers, vinyl sleeves, lyric books, and protest posters. I soon recognised this style to signify unity and the strength found in hope. I hope you, the reader, recognise it across our exhibition and experience the same.

On this record cover, we see Violeta Parra who is seen above the clouds in the sky, the sun shining on her face as she continues to sing and play the guitar beyond the planes of life. Her life, full of both ambition and sadness, reflects those same themes we are exploring at Thinking Inside the Box:1973 - those of ‘conflicto y aspiraciones’, of hope and struggle. While those who drive social change become the symbols of hope and of determination, we must remember that the anguish they carry to fulfil this work is deep. By remembering them, through their words, their music, their lives, we can do just this; we can thank them for what they have done and find the courage to uphold the change they fought for.

Ya no tendrá sus dolencias She will no longer have her ailments

porque se fue de este mundo because she left this world

sumergida en el profundo submerged in the profound

misterio de las ausencias. mystery of absences.

Epílogo, Violetta Parra - Luis Advis

a Visit to the Liverpool Music Archive

A reflection on our visit to The Popular Music Archive at the University of Liverpool by Mayu Taniguchi.

BY MAYU TANIGUCHI

FEBRUARY 2023

As students, we are often encouraged to challenge conventional ways of thinking, to bring renewed ideas and fresh perspectives; to “think outside the box.” Well, for this project, not entirely; it places greater emphasis on learning from the past (what is already inside the box) to think about the future.

Thinking Inside the Box: 1973 is a student-led, co-curricular project that engages with a variety of historical materials from Latin America, particularly from the mid-to-late 20th century, ranging from protest music to political pamphlets and solidarity posters. It is currently running between the Universities of Leeds, London (King’s College and Queen Mary) and Liverpool. With the support and expertise of Dr. Anna Grimaldi and Dr. Simon Rofe, undergraduate and postgraduate students at the University of Leeds have been exploring archives across the UK and digitally, building up knowledge about Cold War Latin America and drawing from their experience to shape a series of events, including a multimedia exhibition, a poster-printing workshop, and film screenings from April this year.

My name is Mayu, and I am writing this article to share my experience as one of the content creators for Thinking Inside the Box: 1973. I am currently in the third year of my undergraduate degree in International Relations and Spanish, specialising in human security. I got to know about the project through a friend of mine from Peru, who is now one of the team members running our Instagram (see more here: @thinkinginsidethebox.leeds). I decided to join the project because I am interested in Cold War history but have little understanding of how it played out in Latin America. The Cold War is often discussed at the macro-level, generalised as a tension between Capitalism and Communism, namely the US and the Soviet Union; a lot less is known about how “the people” (el pueblo, in Spanish) lived through and survived the period. I have also been curious to learn more about the deeply rooted and complex relationship between the United States and Latin America since watching Tom Clancy’s Jack Ryan, a show that touches on the present day United States’ intervention in Latin American politics.

While every member of the team has their own background and reasons for getting involved in the project, we are now working together to expand our knowledge and draw inspiration from a series of archive visits to launch an enriching, exciting series of events. So far, we have planned two in-person archive visits: The Popular Music Archive at the University of Liverpool and the Latin American Political Pamphlets Collection at the University of London’s Senate House Library. We have also carried out a workshop to explore the digitised collection of Tallersol, a cultural centre in Santiago, Chile, founded in 1977.

—

Our first destination this year was The Popular Music Archive at the University of Liverpool. We were welcomed by Dr Richard Smith, who guided us to a room full of vinyls, CDs, cassettes, books of song lyrics and poetry, and posters. The materials formed part of a collection relating to hope and struggle in Latin America, with a particular focus on movements for democracy and freedom in Chile. All of us were amazed by the variety of colourful, striking visuals – certain artworks reminded me of cubism with their vivid primary colours and range of motifs. Some contained the iconic clenched fist, raised in the air, while others depicted birds, their large wings spread wide as if trying to break free from their cage, the canvas, and fly towards freedom. It was my first time doing archival research and even though I felt like I was jumping in the deep end without enough prior knowledge, the experience was exhilarating. By looking through and combining the images, lyrics, and sounds, I was able, step by step, to build my own multi-dimensional picture of the events and people I was trying to understand. It was a different way of learning - unlike reading a textbook that packs everything neatly, I was exploring and discovering the hidden contents of the archive. The further I looked the more it felt like peeling back the layers of a big onion that could go on forever – I could see how even a single event of the past could take years to understand this way.

One of the most significant things I learned that day was the about the life story of Victor Jara, a Chilean folk singer who was killed during the Chilean military coup of 1973. As well as a famous singer and songwriter, he was an engaging political activist whose music encouraged and generated civic solidarity to confront the repressive military regime curtailing the democracy and freedom of the people of Chile. According to a biography I found at the archive, Victor Jara said:

“My songs, they are what I feel, they are about my life. But I am a peasant and so they are about millions of people, about suffering, but also sometimes victory.”

Music and songs were a fundamental way to show resistance when the regime banned freedom of expression and censored political literature. More importantly, it contributed to creating a sense of emotional connection and community among people, especially victims of the regime. Although Victor Jara was brutally murdered by the military government during the first few days of the regime, they could not silence his voice because his songs represented the shared experience of all those suffering from poverty, oppression, and fear, not only in Chile, but across the world. To this day, Victor Jara’s music is played and sung by the hundreds and thousands of people from all over the world who are repressed by authoritarian regimes.

Our experiences so far have inspired us to explore the overarching theme of “Hope, Struggle and Solidarity.” The Cold War period in Latin America was violent, heartbreaking, and bleak; it was a period of many struggles… against dictatorship, against authoritarianism, against political imprisonment and torture, and against poverty and inequality. But these were also struggles of hope for a better future. The artworks, songs, and stories we will explore as part of Thinking Inside the Box 1973 are uplifting and full of passion for life, they shine a light through the darkness and encourage optimism when the struggle against oppression seems hopeless, they generate solidarity based on shared hopes that democracy and freedom are soon to come. By opening these boxes of archives we intend to reawaken these struggles of hope and stand in solidarity with them; learning from the past to struggle for a better future.

previous events.

-

Our main, month-long exhibition at University of Leeds. Launch date, 18th April.

This exhibition explores the theme of “Hope, Struggle and Solidarity.” The Cold War period in Latin America was violent, heartbreaking, and bleak; it was a period of many struggles… against dictatorship, against authoritarianism, against political imprisonment and torture, and against poverty and inequality. But these were also struggles of hope for a better future. The artworks, songs, and stories we present as part of this exhibition do not just deal with protesting human rights violations. They are uplifting and full of passion for life, they shine a light through the darkness and encourage optimism when the struggle against oppression seems hopeless, they generate solidarity based on shared hopes that democracy and freedom are soon to come.

-

LOCATION - Left Bank, Leeds

DATE - Wednesday 5 April to

Friday 5 May 2023An exhibition of political pamphlets reflecting Hope, Struggle and Solidarity in Chile in the 1970s. A parallel to the exhibition hosted at the University of Leeds.

-

LOCATION - Snug space, Hyde Park Book Club

DATE - Thursday 13th April 2023

An informal political poster-making workshop that invited participants to drop in and make a poster about what felt urgent to them. Art materials and revolutionary tunes provided.

-

LOCATION - University of Leeds

DATE - Thursday 20th April 2023

In this guest lecture, Prof. Rodrigo Patto Sá Motta offered an assessment of the year of 1973 in the context of Latin America by exploring the commonalities and particularities among different southern cone military dictatorships. Taking 1973 as a landmark, the guest lecture analysed the objectives and interests that led certain social groups to support the dictatorships and their tools of repression, as well as the impact these authoritarian regimes had on regional and global history. Now that fifty years have passed, can we consider that democracy in the region is durable? Have the structural and contextual elements that gave rise to the authoritarian wave of the 1960s-70s now been overcome?

-

DATE - Friday 21st April 2023

As part of the Thinking Inside the Box: 1973, Anna Grimaldi discussed her recently published book, Brazil and the Transnational Human Rights Movement, 1964-1985. This event explored how solidarity for Brazil contributed to the global human rights movement of the 1970s. Inspired by the theme of hope and solidarity, Anna presented a range of protests, petitions, posters, and other cultural, artistic, and media-based campaigns to understand how the language of human rights shaped and was shaped by solidarity for Brazil. She argued that by prompting the international community to join the fight against dictatorship, solidarity for Brazil reframed the debate on human rights itself, stretching the concept beyond mainstream interpretations to centre on a series of hopes: hopes for social, economic and cultural rights; equality; education and healthcare; the rights of marginalised groups; land redistribution; resource sovereignty, working conditions; and autonomous development. Anna showed how these hopes and struggles were disseminated through networks of exiles, catholic activists, journalists and academics between Brazil and Western Europe, who drew from the Latin American experience to challenge mainstream narratives of human rights from below.

-

DATE - September 2023

LOCATION - Embassy of Chile, London

The Embassy of Chile in the United Kingdom, King's College London and the University of Leeds, are pleased to invite you to the launch of the exhibition Thinking inside the box: Chile, 1973.

The opening shall include an exhibition of political posters from the project Hope, Struggle and Solidarity and a performance by King’s Brazil Ensemble.

See images of the event below.